200 years of Chinese settlement

This year marks 200 years since the first Chinese migrant arrived in Australia back in 1818.

This year marks 200 years since the first Chinese migrant arrived in Australia back in 1818.

The first recorded Chinese settler was Mak Sai Ying – also known as John Shying – who arrived in NSW 1818 and, after a period working on farms, in 1829 became the publican of The Lion at Parramatta.

John Macarthur, the prominent pastoralist, employed three Chinese people on his properties in the 1820s and it’s believed the way ethnic Chinese made it to Australia was from the new British possessions of Malaya and Singapore.

Many British east India ships used Australia as a port of call on their trips to and from buying tea from China and the ships had Chinese crew members.

It is very probable that some of these crew, and possibly passengers also, left the ships in Sydney and settled in the new colony.

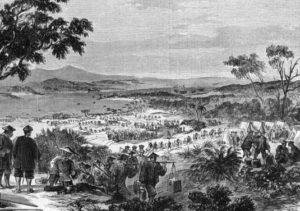

Between 1851 and 1860, about seven per cent of more than 600,000 migrants who arrived in Australia were from China.

Xenophobic hostility toward the newcomers focused on the Chinese, who were regarded as a threat to wages and employment, according to the Department of Immigration’s history on migration to Australia.

The tension resulted in anti-Chinese riots which resulted in several deaths, leading to the colonies’ first restrictions on immigration, targeting Chinese people.

Chinese settlers first came to Victoria in large numbers hoping to strike gold. Most were men contracted to agents who sponsored their voyages, and they faced years of difficult repayments. They also sent money back to their families in China.

By 1861, the Chinese community was thriving with Melbourne’s Little Bourke Street a bustling centre for Chinese cultural and business activity.

As the gold ran out, many Chinese settled as market gardeners or farm hands.

Some set up small grocery stores or fruit and vegetable-hawking businesses in country towns. Others worked around Melbourne in a variety of pursuits, including import-export businesses, laundry operations, cabinet making and in medicine.

Many Chinese religious and cultural organisations were established, and Chinese New Year celebrations became a highlight in many towns in Victoria.

Chinese immigration had been restricted by Government policy from as early as the 1850s, but it was the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act – also called the White Australia Policy – that posed a significant barrier to the entry of non-Europeans, including the Chinese.

The act saw the use of a now infamous ‘dictation test’ which required would-be migrant to submit to a 50 word dictation test that could be in any European language.

The Chinese community protested against prejudice, however, and activists such as Loius Ah Mouy and Lowe Kong Meng highlighted the important economic and social contributions made by members of their community.

Finally, policy restricting the migration of non-Europeans was lifted in the 1970s, and trade links with China were subsequently strengthened.

Between 1986 and 1991 the China-born population in Victoria more than doubled to over 20,000. This number was largely due to the many Chinese students seeking citizenship and asylum after the repression of student demonstrations at Tiananmen Square in 1989.

In 2011, the Census recorded 93,895 China-born people in Victoria. In recent years many professionals have migrated from China, including scholars, doctors and business investors. Many more live in Victoria temporarily as students.

They have continued a long and proud history of a Chinese community that has made an important contribution to Victorian and Australian life.

Now, a new arts initiative is exploring the link between Chinese and indigenous Australians.

Jason Wing is a Sydney-based artist, descended from the Biripi Aboriginal people from the modern Taree region on his mother’s side, and hailing from the Canton (Guangdong) province of China on his father’s.

“I tell people I’m 100 per cent Chinese, 100 per cent Aboriginal, 100 per cent Australian, and most people can’t really grapple with that. But that’s how I’ve always felt,” Mr Wing said.

He was largely raised by his paternal grandfather Stan Wing, a former Australian Army Major born in Sydney to Chinese migrant parents, in a house in Cabramatta, Sydney, adorned with Chinese paper cuttings.

Wing’s artworks such as “ABC” (Aboriginal Born Chinese) reflect how he has combined traditional Chinese art forms with the legacy of his Aboriginal heritage.

While Wing saw a rich relationship between Chinese and Indigenous cultures in Australian history, he lamented that this was another part of the nation’s untold past.

Mark Wang, Director of the Chinese Museum in Melbourne, says both societies were marginalised and therefore had things in common.

“There was a lot of intermarriages between Chinese men and other ethnicities, so that’s how that relationship between Aboriginal and Chinese people started,” he said.

Jason Wing and Mr Wang believe this was the beginning of a strong cultural bond between Indigenous and Chinese communities, which they are eager to capture in future artwork and exhibitions.

Laurie Nowell

AMES Australia Senior Journalist