Poland and Iran – a tale of two refugee journeys

It’s a bizarre quirk of history and one that lays bare the self-serving and populist forces at work in geopolitics.

During World War II thousands of Poles fleeing either the Nazis or Stalin’s brutal purges sought shelter in Iran.

But today, Poland has closed its borders to refugees seeking shelter from conflicts and brutal regimes in the Middle East.

One of the refugees from almost eight decades ago has published a memoir about her experiences.

One of the refugees from almost eight decades ago has published a memoir about her experiences.

In 1939 Helena Stelmach, 86, was caught between German soldiers invading Poland from the west and Soviet troops occupying the east of the country.

Stalin deported more than one million Poles to Siberia, and Ms Stelmach’s family was among them. Soviet soldiers arrested and imprisoned her father in Poland, while eight-year-old Helena and her mother were forced to leave their home.

“It was midnight when they came for us,” she says in her memoirs.

“First, they sent us to a church, and then to Siberia. All we took with us was a suitcase with an old rug, some pieces of jewellery and family photos.”

In her diary, published in Farsi under the title ‘From Warsaw to Tehran’, she told how Polish refugees died every day in Siberia from the freezing weather, maltreatment and disease.

Her family’s ordeal lasted two years, until Hitler attacked the Soviet Union, prompting to release captive Poles. Many moved south to Iran, and to Lebanon and Palestine – then under British control.

In 1942 tens of thousands of Poles arrived in the region seeking refuge. This year, Poland has shut its doors to refugees going in the opposite direction.

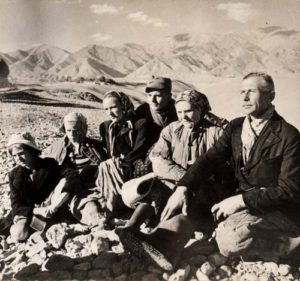

The Polish influx is not something openly discussed in Iran to this day but in 1942, about 120,000 from Poland began their exodus to Iran from remote parts of the Soviet Union.

The Polish influx is not something openly discussed in Iran to this day but in 1942, about 120,000 from Poland began their exodus to Iran from remote parts of the Soviet Union.

The Poles entered Iran from the port city of Anzali on the southern coast of the Caspian Sea. Soviet ships docking in Anzali were packed with Polish refugees – but many had died along the way from typhus, typhoid and hunger.

Ms Stelmach’s mother was a nurse so the family avoided disease and hunger.

In return for taking care of the ship captain’s sick son during their journey across the Caspian the family received food.

There are stories about Polish refugees being loaded on to trucks for the trip from Anzali to Tehran having objects thrown at them by Iranians.

The frightened refugees at first thought they were being stoned, but soon noticed that the objects were not rocks, but rather cookies and candies.

In Tehran, the refugees were accommodated in four camps; even one of the private gardens of Iran’s shah was transformed into a temporary refugee camp, and a special hospital was dedicated to them.

Polish refugees launched a radio station and published newspapers in their mother tongue. They entered into Iran’s art scene and, as with other waves of immigration, their food appeared on the menus of their host communities. The pierogi, a Polish dumpling, is still very common in Iran.

Ms Stelmach met her Iranian husband Ali after her mother rented a shop in central Tehran selling Polish dishes while Ali worked in a neighbouring shop.

She helped Ali learn English and their relationship grew.

Iran and Poland have both been transformed since 1942. World War II ended, an Islamic revolution took place in Iran, the Iron Curtain fell, and Poland became part of the European Union.

Yet, the Stelmachs decided to remain in Iran.

They visited their former homeland several times, and even received the Order of the White Eagle, one of Poland’s highest honours.

When Ms Stelmach’s mother died in 1983, she was buried in the same cemetery as the casualties of the Polish exodus in 1942.

Laurie Nowell

AMES Australia Senior Journalist