South Sudan – five years of war in the world’s youngest nation

This week marks five years since a devastating civil war broke out in the world’s youngest nation, South Sudan, leaving an estimated 400,000 people dead and more than four million displaced.

This week marks five years since a devastating civil war broke out in the world’s youngest nation, South Sudan, leaving an estimated 400,000 people dead and more than four million displaced.

South Sudan was born less than 10 years ago after a decade-long conflict and secession battle with Sudan ended in 2011.

But since gaining its independence, it has barely seen two full years of peace.

The country has been ravaged by conflict since political tensions between President Salva Kiir and Vice President Riek Machar flared into full-scale civil war in 2013 – just two years after independence from Sudan.

Despite a recent shaky ceasefire, the economy and infrastructure remain decimated.

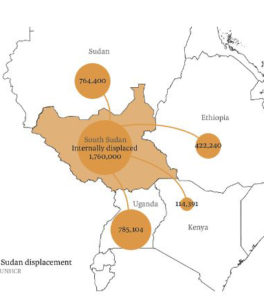

Half of the almost million population need humanitarian assistance and 4.5 million people are displaced, either within the country or abroad.

Aid agencies say about 19,000 children are involved with armed groups, and the country has the world’s highest proportion of children out of school.

In December 2013, political in-fighting between President Salva Kiir and his deputy Riek Machar escalated, soon including other opposition groups and spreading beyond the capital.

The conflict has seen armed militias aligned along ethnic lines engaged in combat and attacking civilians at will.

In the last five years, of the nearly 400,000 people who have died, at least half have been victims of the conflict and the rest from hunger and disease.

Over the same period, 1.9 million others have been internally displaced, and more than 2.4 million people live as refugees in neighbouring countries such as Uganda, Ethiopia, and Sudan – most of them women and children.

Numerous ceasefires and attempts at durable peace agreements have been negotiated since 2013, but most have not lasted.

A peace deal was signed in 2015 but collapsed less than a year later, forcing Machar to flee the country.

The war has fragmented into a myriad of inter- and intra-communal conflicts, incorporating previously localised disputes over land, resources, and power.

Ethnic divisions have also become more pronounced – especially since 32 new states were established – and traditional front lines have become flexible with widespread guerrilla warfare involving numerous militias.

A new peace agreement signed between the warring parties in September has brought cautious optimism that this time the peace will last.

But despite the deal, NGOs say, in local areas armed attacks have continued with many civilians afraid to leave Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps and return to their villages.

And refugees in neighbouring countries are pessimistic, saying they think the agreement is more about political manoeuvring than about peace.

One result of the prolonged war South Sudan’s meal-to-income ratio is 300 times that of industrialised countries and hundreds of thousands of people are in need of food aid. Parts of the country have been declared to be in famine.

The UN says many communities require help with food, healthcare, education, protection, water and sanitation, and other basic services that the government is unable to provide.

As fighting continues, peace seems elusive to many South Sudanese. But the real challenge into the future, even if peace does hold, will be how to rebuild lives, livelihoods and public services in a country where aid organisations have struggled to fill the gaps for years.