Youth unemployment hotspots identified

Around 250,000 young people are unemployed across Australia with some regions seeing youth unemployment rates as high as 25 percent, according to new research.

Around 250,000 young people are unemployed across Australia with some regions seeing youth unemployment rates as high as 25 percent, according to new research.

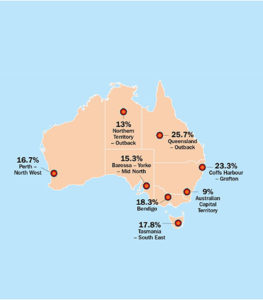

Regional areas in NSW, Victoria and Queensland have among the highest rates of youth unemployment in the country, peaking at more than five times Australia’s overall unemployment rate.

Coffs Harbour has the highest youth unemployment rate in NSW with a rate of 23.3 per cent. It is second only to outback Queensland with a rate of 25.7 per cent, which is more than five times the overall unemployment rate of 5 per cent, according to the latest jobless youth snapshot from anti-poverty group The Brotherhood of St Laurence.

Bendigo in Victoria has a youth unemployment rate of 18.3 per cent and the rate in Shepparton is 17.5 per cent. The New England region of NSW is also among the top 20 youth unemployment hot spots with a rate of 14.3 per cent.

The Brotherhood’s Youth Unemployment Monitor says that while the modern economy represents new opportunities for jobseekers, it also poses risks for young people who often have little or no work experience.

“Young people without training opportunities or higher educational qualifications face a double jeopardy,” it says.

Young people from culturally and linguistically diverse communities are among those vulnerable to unemployment.

Madelin Ly, 21, from Cairnlea in Victoria, lives in Melbourne’s west, which has a youth unemployment rate of 15.5 per cent.

She graduated with a degree in animal and veterinary biosciences from La Trobe University in 2017 but has been unable to get a permanent full-time or part-time job since then because of her lack of work experience.

She is taking part in the work for the dole program doing administrative duties for a not-for-profit organisation while she continues her search for a permanent job. She is also volunteering at an animal hospital.

“A lot of employers want you to have experience before you can gain it through proper employment. That’s been one of the challenges,” Ms Ly said.

“I’ve had two jobs – as a waitress and [last year] I was employed at the lost dogs home as an animal attendant.

“I’m prepared to work anywhere, however ideally I would like a job within the animal industry.

“I think one of the challenges is that the industry is quite competitive.”

Conny Lenneberg, executive director of the Brotherhood of St Laurence, said that despite 28 years of continuous economic growth, many young people were locked out of the labour market.

“We remain deeply concerned at how young people without qualifications and skills or parental support are tracking,” Ms Lenneberg said.

“To secure the future labour force and create opportunities for decent work, we need structural solutions that are finely tuned to local job markets and infrastructure.”

Labour market economist Dr Ian Pringle says that a lot of activity in regional Australia that is described as economic growth are really micro-businesses that don’t employ anyone and the regions also have pockets of high disadvantage.

“We see entrenched disadvantage in some of these places and generational welfare dependency where families are stuck in a welfare cycle,” Dr Pringle said.

“Social services address things like homelessness, gambling or drug issues, but they do not naturally marry up with employment services,” he said.

“You might fix some issues in people’s lives, but if there are no opportunities to take the next step into employment it is easy for them to fall back into problems.

“And lots of employers say that people in this state are just not job ready.

“So we have a gap here and we need to help these people bridge it.

“There are job opportunities in allied health, aged care and disability services and vehicle component manufacturing, but these jobs are beyond young people who have the sorts of issues we’re talking about,” Dr Pringle said.