The refugee crisis – a global stocktake

Today, nearly 71 million people – almost three times the population of Australia – have been forced to flee their homes.

This displacement is now the largest in recorded history constitutes a complex picture of conflict, persecution and statelessness that has created human misery on an unprecedented scale while also offering up political opportunities for populist xenophobic leaders.

Despite this, and rising numbers of displaced people, there are some positive developments in the struggle to find solutions to the global refugee crisis.

Despite this, and rising numbers of displaced people, there are some positive developments in the struggle to find solutions to the global refugee crisis.

Refugees

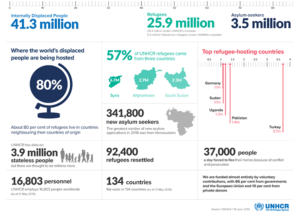

Just over 26 million of the globe’s displaced are refugees—individuals who, because of a legitimate fear of persecution or violence for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group, have fled their countries. Half of all refugees are under 18 years of age.

Two-thirds of all refugees worldwide come from just five countries: Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Myanmar and Somalia.

Refugee-hosting countries provide temporary protection, as opposed to permanent resettlement. The top refugee-hosting countries are: Turkey (3.7 million); Pakistan (1.4 million); Uganda (1.2 million); Sudan (1.1 million), and; Germany (1.1 million).

Asylum seekers

Asylum seekers

There are about 3.5 million asylum seekers across the globe. These are individuals who seek protection in a specific country and must wait to be recognised by that country as a refugee, with the attendant protections due to well-founded fear of persecution and violence.

Internally Displaced Persons

About 41 million people are internally displaced persons within their own countries. These are individuals who have fled their homes because of internal strife or natural disaster but have not crossed an international border.

IDPs remain under the legal protection of their own governments, and unlike refugees, are not eligible for international legal protection, nor many types of aid. They are the largest group assisted by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

Countries with large internally displaced populations include Colombia, Syria, Democratic Republic of Congo and Somalia.

What international law says

The basis of international refugee law is the 1951 Geneva Convention. Adopted in the wake of WW II, this agreement defines what a ‘refugee’ is and spells out the legal protection and assistance that must be given to refugees by the 145 countries who have signed the Convention.

The Convention also states that refugees must respect the laws and regulations of the host governments and allows that some categories of people, for example: war criminals, do not qualify as refugees.

In 1967, the Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees expanded the scope of the Convention’s protection to events beyond Europe and after 1951, as the challenge of displacement was recognised as an increasingly global phenomenon.

The Protocol has 146 signatories, including Australia. Forty-three United Nations member states – including India, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, malaysoa and North Korea – are not signatories to either the 1951 Convention or 1967 Protocol.

Next month, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) will hold the first ever Global Refugee Forum in Geneva.

This gathering of UN member states, together with private businesses, non-profit organisations and non-governmental organisations will gather to address the current refugee situation.

The meeting follow the 2018 Global Compact on Refugees – the international community’s statement of intent to improve the world’s response to the refugee crisis by ensuring that refugees and the nations hosting them receive the support they need.

The compact was endorsed last December by 181 member nations. Only Hungary and the United States did not endorse the compact, with the US citing concerns over ‘sovereignty’.

The compact has four objectives: to share responsibilities for refugees more equitably; to enhance refugee self-reliance; to expand access to third-country solutions (i.e., permanent resettlement or other opportunities such as scholarships or work permits), and; to support conditions in countries of origin for safe, voluntary, dignified repatriation.

The compact included in its remit regular meetings to assess progress toward its goals.

This December’s meeting is the first. It will see the nations and other stakeholders exchange information on ‘good practice’ as be a vehicle for pledges and contributions within six focus areas.

The areas are: responsibility sharing; education; jobs and livelihoods; energy and infrastructure, and; solutions; protection capacity

One of the hopes for December’s meeting is that more nations and other actors will join the response to the refugee crisis as donors, hosts and partners.

The compact’s proponents hope to enlist the help of what is termed the ‘missing middle’ – those states that could either contribute more or host more refugees.

In 2018, 76 percent of UNHCR’s budget came from the top ten donor states, with 38 percent from the United States alone, and 60 percent of the world’s refugee population lived in just 10 countries.

Traditionally, the US has led the world in refugee resettlement. Until 2017, it resettled more refugees each year than the rest of the world’s countries combined.

But since the Trump administration took office, its refugee intake has collapsed. Last year Canada was the lead in settling refugees on a per capita basis with 756 refugees settled for every million people.

Australia took in 510 refugees per million people, Sweden 493 and Norway 465.