Global population growth dips – UN report

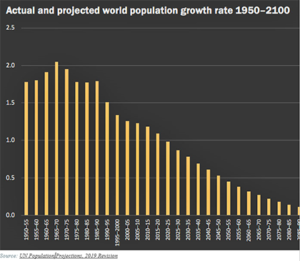

The United Nation’s latest world population projections show that global population growth is slowing more quickly than anticipated.

By 2100, the United Nations believes, the world’s population – now around eight billion – will be just under 10.9 billion. That’s 300 million fewer people than it forecast in 2017. And even that reduction assumes the decline in fertility in recent decades will slow markedly over the next fifty years.

The UN’s World Population Prospects 2019 report show a continuing decline in the “global fertility rate” – the number of live births per woman across the world.

The UN’s World Population Prospects 2019 report show a continuing decline in the “global fertility rate” – the number of live births per woman across the world.

Another report into fertility and family planning says the global rate declined from 3.2 per woman in 1990 to 2.5 in 2019, with Sub-Saharan Africa, the region with the highest fertility levels, recording a fall from 6.3 births per woman in 1990 to 4.6 in 2019.

Fertility in Northern Africa and Western Asia was down from 4.4 to 2.9, in Central and Southern Asia from 4.3 to 2.4, in East and Southeast Asia from 2.5 to 1.8, and in Latin America and the Caribbean from 3.3 to 2.0.

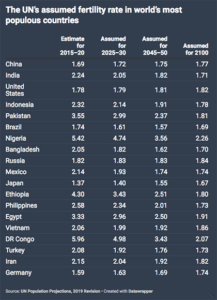

The UN’s median population projection assumes global fertility will continue to decline to below replacement levels (or just under 2.1 babies per woman) from 2065 onwards. That adds up to a reduction of between 0.4 and 0.5 babies per woman over a period of forty-five years.

The case of India illustrates the UN’s assumptions. Its fertility rate has declined from 5.6 babies per woman in 1970 to around 2.24, a fall of almost 3.4 babies per woman. The UN report says that India’s figure will decline to below the replacement rate by 2030, but much more slowly than over the past fifty years.

It assumes a similar trend in Indonesia, Bangladesh, Iran, Turkey, Vietnam, Mexico and to a lesser degree Pakistan.

Of the world’s most populous countries, the UN assumes only Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo will remain at or above replacement levels for all of the twenty-first century. It expects the fertility rate in Ethiopia to remain high until 2050 but to then fall to below replacement levels. Given their relatively young populations, these countries are projected to see continued strong population growth for the rest of the century.

Of the world’s most populous countries, the UN assumes only Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo will remain at or above replacement levels for all of the twenty-first century. It expects the fertility rate in Ethiopia to remain high until 2050 but to then fall to below replacement levels. Given their relatively young populations, these countries are projected to see continued strong population growth for the rest of the century.

On the other hand, the UN has assumed that the fertility rates in the world’s five main economic and/or military powers (the United States, China, Russia, Japan and Germany) will rise for the rest of the century.

In the United States the fertility rate has declined in each of the past four years. The 2018 figure of 1.73 babies per woman was the lowest on record for that country, and already substantially below the UN’s estimate of 1.78 for the period 2015–20, according to the report.

The United States’ relatively high rate of immigration, projected forwards, means that its population is expected to rise to over 433 million by 2100, an increase of 31 per cent on the 331 million it recorded in 2019.

The UN report says China’s fertility rate will rise steadily for the rest of the century. In 2019, China recorded its lowest number of births since 1961, when it had a very much smaller population.

Birth numbers there have now fallen for three years in a row, and some academics argue that China’s actual fertility rate is much lower than official reports.

Even using official statistics and the rising-fertility assumption adopted by the UN, China’s population is projected to peak in the early 2030s and then continuously fall by around 375 million by the end of the century, a 26 per cent decline.

Russia’s fertility rate, meanwhile, hit a low of 1.25 babies per woman in 2000. It has subsequently been rising and was estimated by the UN at 1.82 for the period 2015–20.

Despite the assumed increase in fertility, though, Russia’s population is projected to decline by 14 per cent, from 146 million in 2020 to 126 million, by the end of the century, the UN report says.

Japan’s population is projected to fall from 126 million in 2020 to a surprising seventy-five million by the end of the century. That represents a 40 per cent reduction in population and relies on the fertility rate rising from 1.37 babies per woman in 2015–20 to an unlikely 1.67 babies per woman by the end of the century.

Japan’s population could decline by much more than 40 per cent by 2100 if its fertility rate remains around current levels, mainly because of its already very aged population.

Germany’s population is projected to decline from eighty-four million in 2020 to seventy-five million in 2100, a reduction of around 11 per cent. This relies on fertility rising from 1.59 babies per woman to 1.74 — otherwise the decline would be even more significant.

Germany’s net migration rate is projected to fall from a relatively high 0.66 per cent per year in the period 2015–20 to around 0.20 per cent per year for the rest of the century.

Low fertility rates are accelerating the ageing of many country’s populations, causing economic and financial headaches.

Globally, 703 million people were aged sixty-five or over in 2019. The UN projects this to rise to 1.55 billion by 2050. The percentage of people in that age group has grown from 6 per cent worldwide in 1990 to 9 per cent in 2019, and is projected to increase to 16 per cent in 2050.

These percentages are higher in developed nations. Developing nations, in contracts, have higher fertility rates and lower life expectancy.

The number of people aged eighty and over is growing even faster, with the UN projecting this cohort to triple in size to 426 million by 2050.

The UN’s next revision of world population prospects, due in 2021, will almost certainly take in to account of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Only a very small acceleration of the decline in global fertility rates is needed for the trend in the UN’s recent figures to record negative growth in the latter years of this century rather than the currently projected positive growth.

If global fertility rates were to decline at the same rate as the past twenty-nine years, the global population would be sharply in decline well before the end of this century.

The obvious question than, is that if the major economies are unable to increase fertility rates will they turn to migration policies to slow the ageing of their populations?