Where will Afghanistan’s refugees go?

Images of thousands of Afghans desperately trying to flee their country through Kabul’s international airport sparked an international outcry.

And as the US and its allies, including Australia, completed their operations to evacuate people from Kabul, the question remains: what will happen to Afghans wanting to leave their country?

More than 47,000 Afghan civilians and at least 66,000 Afghan military and police forces have died in the 20-year-old Afghanistan war.

More than 47,000 Afghan civilians and at least 66,000 Afghan military and police forces have died in the 20-year-old Afghanistan war.

With the Taliban takeover of Kabul, there is a growing concern for the safety of Afghanistan’s women and girls, ethnic minorities, journalists, government workers, educators, and human rights activists.

The UN refugee agency UNHCR says that up to half a million Afghans could flee their homeland by the end of the year.

More than 20,000 people have already left, seeking sanctuary overseas, but for many more there is not a clear way out.

The US government is reportedly planning to relocate 30,000 Afghan refugees, Canada has pledged to take 20,000, Australia 3,000 and Uganda 2,000.

In Europe, Germany has offered to accept 10,000 asylum seekers but France has yet to commit to a number. Russia, Austria and Switzerland have all refused to be involved.

Hungary has reluctantly agreed to accept “a few dozen” families but President Viktor Orban has said: “Let’s send assistance there, not bring trouble here”.

Other countries committing to take in Afghans temporarily in small numbers include Albania, Qatar, Costa Rica, Mexico, Chile, Ecuador, and Colombia.

Other countries committing to take in Afghans temporarily in small numbers include Albania, Qatar, Costa Rica, Mexico, Chile, Ecuador, and Colombia.

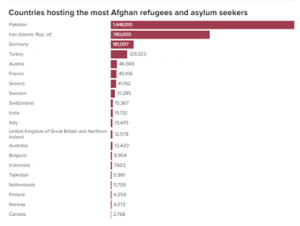

Ultimately though, most Afghans able to leave the country will do so on foot, walking across remote border posts into Pakistan and Iran.

While the UNHCR has appealed to other neighbouring countries to keep their borders open for those seeking safety, the options of Afghans wanting to leave seem slim.

There seems to be little willingness across Central Asia, Iran and Turkey to accept Afghan refugees fleeing their country’s new Taliban regime.

So, as things stand, most Afghans trying to make it to a neighbouring country will probably head to either Pakistan or Iran – with many intent on moving on to Turkey and then Europe.

Although the Red Crescent Society in Iran has claimed to have set up six camps along the border, reports from there say people entering seeking asylum were being sent back.

Along Iran’s border with Turkey, the Turkish government is quickly putting us a concrete wall.

UN figures say Iran hosts about 800.000 Afghans but other estimates say up to 3.5 million there unofficially.

Turkey has cut migration deals with the EU in the past and might do so again and host millions of Afghans in return for payments.

But with an election due in 2023, and rising opposition among the population to allowing in more refugees, this may be a step too far.

Turkey already hosts more refugees than any other country worldwide.

Officially, there are only around 100,000 Afghan refugees in Turkey but the country hosts a total of 3.7million refugees.

Other estimates says there is a total of ten million migrants in the country, including 5-6 million Syrians and 1-1.5 million Afghans.

Pakistan, which shares a 1,640-mile land border with Afghanistan, has long been a haven for large number of Afghan refugees, especially minority groups, even though it is not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention.

After the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, following the conflict ignited by the rise of the Mujahideen, 1.5 million Afghans had become refugees. By 1986, nearly 2 million Afghans had fled to Pakistan.

Since 2002, the UNHCR had repatriated nearly 3.2 million Afghans home, but in April 2021 it reported that more than 1.4 million Afghan refugees remained in Pakistan due to ongoing violence, unemployment, and political turbulence in Afghanistan.

Earlier this month Pakistan deployed its army along its border with Afghanistan to block an anticipated wave of refugees from entering its territory.

While Uzbekistan offered the US and others airports for the processing of Afghan refugees transiting elsewhere, there is a lot of pressure from Uzbeks to not allow any significant number of those escaping Afghanistan to settle.

Uzbeks fear that militant and terrorist extremists could disguise themselves among a flow of refugees and infiltrate the country, a recent survey found.

Russia is also wary of terrorist infiltration, as it has a largely open border with the Central Asian republics, with President Vladimir Putin questioning whether there could be extremists among the Afghans fleeing.

Tajikistan and Turkmenistan and the other two Central Asian countries that border Afghanistan.

Tajikistan has been taking a small number of refugees from Afghanistan since the Taliban took over. The country said in July that it was ready to accept 100,000 refugees Afghanistan. However, it may come under pressure from Russia to close its border. Russia’s largest military base abroad is located in Tajikistan.

But there are millions of Tajikistanis among Afghanistan’s population of 38 million.

The autocratically controlled ‘hermit nation’ of Turkmenistan is also unlikely to take in any refugees from Afghanistan.

Turkmen government authorities have held talks with the Taliban and with a desperate economic crisis the country needs cooperation from the new rulers in Kabul.

Meanwhile, human rights activists in Mongolia have called on the government to grant asylum to people of the Hazara minority in Afghanistan – who are aid to be the descendants of Mongols.

But the nation is not a signatory to the UN refugee Convention and the government has been silent on the issue.

Given limited numbers of third country resettlement options and the fact that border crossings in the region are more difficult and dangerous than ever, the vast majority of uprooted Afghans will remain within Afghanistan’s borders.

Their significant humanitarian needs, economic and political circumstances and security concerns will shape the next chapter of the country’s strife-torn history.