Journalists carry the torch of freedom

From a small news room and studio in suburban Melbourne a group of exiled Burmese journalists is beaming news, interviews, information as well as hope and encouragement back to the people of their beleaguered homeland.

The group of four are part of the Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), an independent, not-for-profit media organisation and TV channel that has been promoting democracy and human rights in Burma for more than 30 years.

Following the February 2021 military coup, the organisation was banned and some of its reporters locked up for daring to challenge the new regime.

Some DVB journalists have made their way to Australia as refugees and are continuing their work, trying to inform the people of Burma about what is happening in their country and the world despite heavy media censorship by the military.

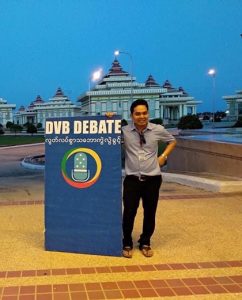

The group’s leader Nay Thwin Nyein was a household name in Burma before the coup.

“Before the coup I worked on DVB’s TV debate program as the moderator. It ran on free to air and satellite TV channels with a focus on politics, human rights, social harmony and the peace process,” Nay Thwin said.

“It was a well-known program, one of the most famous news shows in Burma. We had lots of high profile people debating about political issues in the country,” he said.

“It was a well-known program, one of the most famous news shows in Burma. We had lots of high profile people debating about political issues in the country,” he said.

But the 2021 military coup in Burma coming after a general election in which Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) party won by a landslide, everything changed.

Amid the brutal crackdown led by coup Leader General Min Aung Hlaing, which saw widespread killing and torture of civilians, DVB was banned.

“When the military took control we didn’t know what to do. We knew the military would not allow our content or independent voice,” Nay Thwin said.

“A month after the coup, they cancelled out registration and we became an illegal organisation in my country,” he said.

“We couldn’t work legally or openly any more so all our reporters went undercover. And people like me, who were well known, had to go in to hiding.

“At first I tried to hide in Rangoon, the capital, moving from place to place and staying with friends. At that point there was relative calm and things were peaceful.

“But a few days later the military showed their true colours and cracked down violently on people opposing them. They killed demonstrators and arrested journalists, including some of my friends.

“It became too dangerous for me to stay with my friends so I moved to a rural area,” he said.

“It became too dangerous for me to stay with my friends so I moved to a rural area,” he said.

Nay Thwin found refuge in the Kareni State, home to an ethnic minority group that has long been persecuted and targeted by the Burmese military.

“My plan was to find a safe place to continue my work of reporting the truth about what was happening under the protection of the Kareni militia groups,” he said.

“I was able to stay in a Christian church and tried to continue my work. But there was no internet and only some telephone connections. I tried to report on what was happening but it was difficult.”

It was then that Nay Thwin received am message from DVB’s head office in Oslo that he should try to get to Thailand to join with other colleagues and try to resume their work.

“Some of my colleagues had joined me in the Kareni state and so together we travelled to Thailand illegally,” he said.

“We walked overnight for six hours across some rugged mountains. It was exhausting and scary. When we made it into Thailand we were met by friends with a car and we drove to Chang Mai. We changed cars two or three times – I don’t really remember because I fell asleep.”

Nay Thwin and seven colleagues set up their operation in a house in Chang Mai, producing news content, interviews and debates, mostly delivered online.

Nay Thwin and seven colleagues set up their operation in a house in Chang Mai, producing news content, interviews and debates, mostly delivered online.

“We arrived in Chang Mai just before the Songkran water festival but there were no celebrations because it was during the COVID period. We managed to rent a house and continue our work.

“We were working quietly. We knew we were in Thailand illegally but it was impossible to continue to work in my country so we felt an obligation to try to keep the channel going. We felt we had a duty to let people know what was going on.

“Almost all of the independent media in Burma has been abolished by the regime and they have stopped working. But we felt we couldn’t stop and that our people have a right to know the truth about what is happening in our country,” Nay Thwin said.

“We would receive reports from out undercover reporters in Burma that were smuggled across the border and we would broadcast them back into Burma from Thailand.

“We were like a news service in exile. It was very challenging for us but people in Burma were still receiving news,” he said.

The Chang Mai operation came to an end one morning when the Chang Mai house was raided by Thai policed and immigration officials.

The Chang Mai operation came to an end one morning when the Chang Mai house was raided by Thai policed and immigration officials.

The group were arrested and charged with illegal entry into Thailand. A subsequent court appearance saw them sentenced to seven months in prison and fined. They also faced the even more serious prospect of being sent back to Burma and into the hands of the military.

After the sentencing the group was taken to Bangkok where they expected to be incarcerated in one of the city’s notorious prisons. But at this point the journey of Nay Thwin and his colleagues took an unexpected turn.

“We spent one night in detention in Bangkok and we were expecting to go to jail but the next morning we were told there was a United Nations person waiting for us outside,” Nay Thwin said.

“The people from the UN said ‘you have to have a medical check-up and them we have a form for you to fill out’,” he said.

“When we saw the form, it said ‘Australian Government – Immigration and Citizenship’. It was then we realised the Australian Government was trying to help us.

“No one had told us this was happening but we felt very relieved. We thought we would spend time in prison.

“The next day and immigration officer arrived at the gate of our cell. He told us to bring all our belongings and outside the detention centre a police car was waiting for us.

“At the airport, we met two people from the Australian embassy who explained to us what was going on. At that point we were 100 per cent sure we were safe and we were not being returned to Burma. It was a happy moment.

“If we had been deported back to Burma like some other illegal entrants, we would have been in trouble with the regime. But I think our circumstances were different because we were journalists,” he said.

Since arriving in Australia in June, 2021, Nay Thwin and his colleagues have established a news room and studio in Melbourne, broadcasting news reports and interviews into Burma via DVB’s satellite TV channel.

They have a small TV studio, a sound desk and computer equipment set up in a nondescript suburban house.

“While people are protesting and fighting to keep the rights they have won over the past 15 years, we feel we have a responsibility to support them,” Nay Thwin said.

“People in Burma have got used to having freedoms and rights based on democratic values. The military have taken those rights away so we are fighting back and an open and free media is key to this, along with a values-based civil society.

“I hope democracy will return to my country and I believe the Burmese people will keep fighting until their rights are returned.

“In the meantime, it’s our responsibility as journalists to keep doing our job providing true information as we did before,” Nay Thwin said.

“In the meantime, it’s our responsibility as journalists to keep doing our job providing true information as we did before,” Nay Thwin said.

Another of the group working in Melbourne is news anchor Khin Yupar who arrived in Melbourne from Thailand in April 2022.

She had to flee her homeland to avoid a roundup of reporters by the military early in 2022.

“I was helped to cross into Thailand by the Karen National Army, which is the military force of the Karen ethnic group,” Khin said.

“If I had stayed I could not have continued my work and I may have been locked,” she said.

“For me it was important to continue to do this work and to support the fight for freedom in Burma,” Khin said.

Nay Thwin, whose wife joined him in Melbourne a few months after his arrival, has called on the international community to isolate the Burmese military government.

“I would like to see other nations isolate the Burmese military diplomatically, economically and in terms of business. If they are not given space to breathe, they will stop,” he said.

Nay Thwin also than ked the Australian Government for its support.

“I want to thank the Australian Government and people for helping us to be able to continue our work; and for bringing Burmese activists and journalists here,” he said.

DVB was founded by a science student after the 1988 uprising. It initially operated mostly outside of Burma – based in Oslo and Chang Mai – because of the threat of arrest by the military junta led by General Ne Win.

Since its establishment, DVB has received funding from the Norwegian and Finnish governments. But after the 2010 elections, the first in Burma in 20 years, DVB was able to operate from within Burma.

“Broadcasting our show only became possible after the 2010 election brought some democracy to Burma so we launched the show and it became very successful,” Nay Thwin said.

“The election brought some openness and democracy and the new president, former general Thein Sein allowed DVB to return” he said.

“We were legalised and registered as a mainstream media organisation and we began working in Burma. That all changed in February 2021,” Nay Thwin said.