Olympian’s story raises awareness of human trafficking

When Mo Farah, a four-time Olympic gold medal athlete, revealed recently that he had been trafficked into the UK as a child and then forced to work as a domestic labourer, it made headlines across the world.

In a BBC documentary Farah revealed he was born in Somaliland, north of Somalia, under the name Abdi Kahin.

While UK immigration authorities have said no action would be taken against him, Farah’s revelations have raised awareness about the trafficking of children and put the spotlight on the UK’s and other nations legal approach to trafficking and the treatment of migrants.

One question is: ‘what might have happened to Farah if he weren’t a famous Olympian?’

Last year, at least 10,000 children were trafficked to the UK, and forced into crime, sexual exploitation or domestic servitude, reports say.

In April, the UK government passed the Nationality and Borders Act, which included a highly contentious plan to resettle asylum seekers in Rwanda.

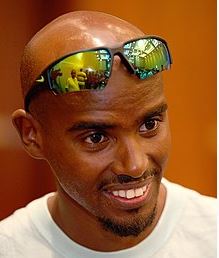

Mo Farah

The legislation also makes it illegal to bring asylum seekers to the UK without proper documentation. The UK-Rwanda agreement has also made it simpler to deport those who falsely claim they are victims of human trafficking.

Anti-trafficking campaigners say the legislation undermines the government’s commitment to tackling human trafficking.

Activists say the UK has made “a lot of progress” in recognising and legislating for victims of child exploitation since Farah was brought to the country in 1993.

But the new laws amount to a rollback that is in line with the increasingly anti-migrant rhetoric emanating from the government and will make it harder for trafficking victims to come forward for fear of negative repercussions from the British state, the activists say.

UK immigration lawyer Maria Thomas who represents victims of trafficking, says “a culture of distrust” in the system that means victims often aren’t believed by officials.

She says it is even more difficult to access protections for those who are vulnerable because of this culture.

Farah took 30 years to be able to speak about his experiences. Advocates say this pattern of late disclosure occurs often in ex-child trafficking victims.

But the new UK laws include a deadline for victims to disclose what happened to them, after which their evidence is deemed less credible.

A parliamentary committee has slammed the clause, saying it undermine the UK’s commitment to combating modern slavery and human trafficking.

Experts say many of the children who are trafficked into the U.K. each year find it hard to settle in the new country.

Government data revealed under FOI shows that in 2019-2020, only 2 per cent of child trafficking victims were granted a discretionary right to stay—which they are entitled to under international law.

Many are instead given temporary visas that expire just before they turn 18, at which point their claim is passed through a different system for asylum seekers that can involve lengthy delays, and where victims are more likely to get a negative decision that risks deportation.

Advocates say the situation will only get worse as the UK government continues to use harsh rhetoric to criticise the overstretched, underfunded public services intended to protect the population from harm.

Conservative Party MPs are overwhelmingly supporting the UK–Rwanda deportation policies despite the late intervention by the European Court of Human Rights that stopped the first scheduled first flight.

The advocates says politicisation of migration in the UK means that children in need of protection are “getting lost in a very adult agenda”.

They says Farah’s story has helped raise awareness about victims of trafficking but this may mean little in the face increasingly draconian immigration laws.