Exhibition remembers efforts to save child refugees

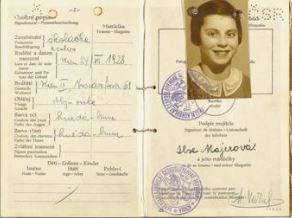

A poignant new exhibition in Berlin tells the story of the Kindertransport, a remarkable effort to rescue mostly Jewish children from the clutches of the Nazis in the lead up to World War II.

About 10,000 children, the majority from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia, were taken to live with foster families in the UK.

About 10,000 children, the majority from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia, were taken to live with foster families in the UK.

The exhibition – titled ‘I said, Auf Wiedersehen’, which opened at the Bundestag, or German parliament, recently – draws on the emotions and experiences of the children, the parents they left behind, and the foster families who took them in.

Often the children were the only members of their families to survive the holocaust. The program was supported, publicised, and encouraged by the British government, which waived the visa immigration requirements that were not within the ability of the British Jewish community to fulfil.

And the British government placed no numerical limit on the program. But it was brought to an end by the start of the Second World War.

Smaller numbers of children were taken in via the programme by the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Sweden, and Switzerland.

The Central British Fund for German Jewry (now called World Jewish Relief) was established in 1933 to support the needs of Jews in Germany and Austria.

In total about 1.5 million Jewish children were murdered by the Nazis.

The Kindertransport is the subject a recent film starring Anthony Hopkins called ‘One Life’.

It tells the story of true story of Sir Nicholas Winton, the “British Schindler”, a stockbroker who assisted in the rescue of 669 children, most of them Jewish, from Czechoslovakia on the eve of World War II.

Winton was born in London 1909 to German-Jewish parents.

His humanitarian accomplishments remained unknown and unnoticed by the world for nearly 50 years until 1988 when he was invited to the BBC television programme ‘That’s Life’, where he was reunited with dozens of the children he had helped come to Britain and was introduced to many of their children and grandchildren.

A key part of the Berlin exhibition are personal “commandments” or guidelines, written in a prayer book by Ferdinand Brann, which he pressed into the hands of his daughter Ursula before she got on the train in Berlin in March 1939.

Ferdinand was deported to Auschwitz and murdered. Ursula would never forget the loving words of advice, which have been reproduced on large placards in the entrance of the Bundestag, including: “Always be grateful to the government of the country you come to for giving you refuge. Be grateful to those who open their home and make it yours.”

Read more here: I said “Auf Wiedersehen”: The 85th anniversary of the Kindertransport to Britain – The Wiener Holocaust Library