Ciao, Yassou, Adieu, Vale… Gough

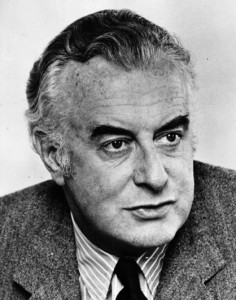

Gough Whitlam, Prime Minister of Australia (1972-75).

History will probably remember Gough Whitlam for his reformist government, for the way he was elected after Labor’s 23-year political banishment and for the way he was dramatically dismissed.

Indeed, since his death on October 21, much has been said and written about those heady days in 1975 and also about reforms like the establishment of Medicare and free tertiary education.

But a lasting legacy of the Whitlam era which hasn’t received so much attention is the wholesale reimagining of Australia as multicultural society and as a self-confident outward-looking nation ready to take its place in the world.

The story of Whitlam and multicultural Australia began in 1971 when, as Opposition Leader, he made a highly unconventional and politically risky trip to China.

When he left these shores, he had no guarantee that the then Chinese premier Zhou Enlai would even meet him and no idea how he would be received.

What eventuated was a two hour meeting with Zhou which would influence China’s emerging relationship with the western world; just a year later US President Richard Nixon also visited the People’s Republic.

Conservatives back in Australia – including right-wing Catholics in the ALP – were horrified by the visit.

Whitlam’s visit was the gamble of a life time. But, it was one that paid off with Gough emerging as a visionary and politician with an electorally appealing ‘crash or crash-through’ style.

As a result, two decades of deep seated hostility toward China was replaced by a reconciliatory approach to the Asian giant that has spawned 30 years of cultural and economic co-operation and has seen China become Australia’s most important economic partner.

In almost his first move as Prime Minister, Whitlam removed the last vestiges of the White Australia Policy, which had effectively precluded non-European migrants coming to Australia.

“I was profoundly embarrassed by it and did all I could to change it,” he told journalist Paul Kelly in 2001 for Kelly’s book 100 Years – The Australian Story.

Whitlam replaced the racist policy with the concept of a multicultural Australian society, which became government policy for the first time.

The government established multicultural radio stations and telephone translation services, and provided special educational support for migrant children.

Whitlam cultivated an outward-looking and pragmatic view of the world that saw the opportunities in engaging with our regional neighbours and confidently embracing them.

This radical shift in thinking has been embraced to various degrees by successive Australian governments and has driven a decades-long national conversation about Australia’s place in the world.

The move was also recognition of the importance of social harmony and tolerance in a rapidly changing world.

Whitlam’s government swept to power in 1972 with the irresistible slogan: “It’s Time”. The party tapped into rising desire for change which had been fomenting during the social and philosophical upheavals of the 1960s.

Whitlam referenced this in his election speech, saying: “It’s time for a new team, a new program, a new drive for equality of opportunity. It’s time to create new opportunities for Australians, time for a new vision of what we can achieve in this generation for our nation and for the region in which we live.”

Sociologist Dr Andrew Jakubowicz says the Whitlam Government’s reforms, beginning with the repudiation of the White Australia Policy and the introduction of a completely non-discriminatory immigration policy, had a profound impact on ethnic communities; but it did not emerge from a vacuum.

“Change had begun in the policies of the preceding Liberal Government and a number of other factors had converged to support the ideologically-based changes instituted by the Federal ALP,” Dr Jakubowicz says.

“For example, a Labor Government had already been in power in South Australia for five years and, as Don Dunstan – later SA ALP Premier – said, ‘was setting the pace in social reform’. This included removing from the entire body of SA law any provision which permitted discrimination on the grounds of race or country of origin.

“Ethnic communities themselves were beginning to flex their political muscle, articulating anger at deficiencies in the government system, particularly in the delivery of social welfare services.

“The rapid increase of migration from countries of Southern Europe, like Italy and Greece, and the concentration of these migrants in the inner cities, had led to the recognition in many circles that these were disadvantaged groups.

“The mainstream press began to focus on the plight of many migrant groups at a time of rising unemployment and to speculate on the potential of the “ethnic vote” to affect the 1972 election results,” Dr Jakubowicz says.

He says the advent of a government with a focus on social justice was not universally welcomed. Many senior bureaucrats and leaders of business, industry and society were concerned about the threat to their oligarchy – their ruling group of archetypal ‘British’ Australians.

For some ethnic groups, too, particularly those who had fled from Communist regimes in Eastern Europe, there was a fear that an ALP government would be ‘soft’ on Communism.

But Dr Jakubowicz cites ethnic leader Pino Bosi as speaking for the majority of immigrants when he said that after 1972 for the first time immigrants could believe they were “not guests, not outsiders, but part of the country.”

But, in the end, will it be history that will judge whether Whitlam is remembered as much for his vision of a tolerant and diverse society as for his unceremonious dismissal?

Laurie Nowell

AMES Senior Journalist