Recording Melbourne’s disappearing west

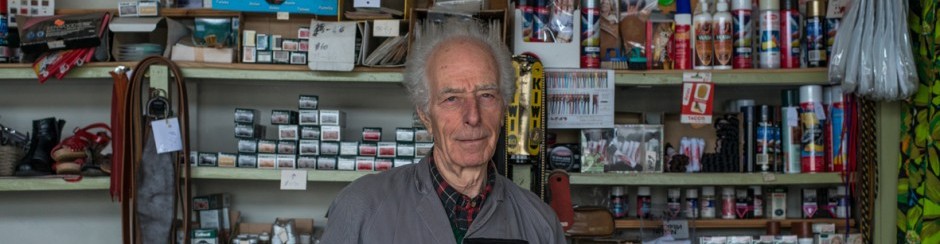

Peter the shoe repairer

Photo: Warren Kirk

Warren Kirk says he lives life “looking in the rear view mirror”.

The accomplished photographer has spent seven years capturing the changes being wrought to Melbourne’s western suburbs by the forces of gentrification, immigration and then property boom.

His photographs have formed a genre he cheekily calls ‘Westography’.

“I guess I’m a nostalgia-head. I’m always thinking things were better back then. I love the charm of the hand-painted signs and the faded pastel colours,” he says.

The west of Melbourne has welcomed successive waves of migrants and refugees over the decades which have bestowed on the region a unique atmosphere and zeitgeist.

Physically, this vast swathe of the city has looked quintessentially Australian – all fibro and corrugated iron.

But behind the double fronted brick veneer walls are thousands of incredible human stories. The stories tell of successive waves of immigrants who came to Australia seeking better lives or to escape persecution, war or worse.

In these archetypal Australian suburbs have lived people from Greece, Italy and other parts of Europe who fled economic austerity or political tyranny in the years after World War II.

They have also been home to the thousands of Vietnamese refugees who came by boat to Australia in the 1970s.

More recently people from the horn of Africa, India and China have made the west of Melbourne their home.

Slowly the ‘fibro’ industrial feel of the area is disappearing; replaced by new modernist dwellings and commercial buildings.

And this is what fascinates Warren Kirk. He has launched a one man mission to capture the disappearing urban landscape and characters of Melbourne’s west in all its fading, chaotic and eccentric glory.

He has amassed about 20,000 photographs of the region – an important record of disappearing generations and our truly suburban way of life.

Warren’s photographs hark back to a time when Australian life and culture was unselfconscious and optimistic.

There are box iron fences and topiary mixed with fading milk bar signs, local barber shops, tailors and shoe repair businesses.

The sign-written ads for products and businesses which are long gone are nostalgic remnants of a pre-digital age.

All the kitsch, tack and bric-a-brac are an almost poignant reminder of the way we once lived.

And Warren is mindful of the importance historically and culturally of being honest and authentic in capturing and presenting his work.

“I’m not trying to force myself into these pictures,” Warren says.

“I don’t ask people to do things or stand a certain way. I’m just photographing what I see in front of me,” he says.

“And I’m mindful that the factories and shops I visit are workplaces so I try not to interfere and I use only available lighting.

“I never change anything inside a factory or shop I’m photographing. I just frame it – chaos included. I love the chaos as it give you a narrative that has the power to bring back memories and evoke emotion,” he says.

“Sometimes when I go inside a house or a shop you can see that nothing has changed for 30 or 40 years.”

Warren says his work is not meant to be a comprehensive document of the west and its people.

“I’m not trying to present of the west in totality – it’s a very large, diverse and complex place.

“I’m just trying to photograph what interests me and I guess I stay within a narrow theme that I would call ‘social photography’.

“I photograph the everyday and the mundane. I like to try to glorify that because it’s important.

“I like to photograph small ‘h’ history; people’s everyday lives, small shops and businesses,” he says.

Warren says he sees beauty in everyday things.

“Some people walk past these things and don’t notice them. But I see this stuff all around me and that’s what I do – I’m an observer not a creator.”

Warren says he gets his pictures by trawling the streets and finding subjects that attract his attention.

“There’s a shoe repairer I photographed who has been in the same shop for 60 years. That just doesn’t happen anymore. Imagine someone having a computer repair shop for that long. It just won’t happen,” Warren says.

“I also love the old barber shops in the area. Some of them are frozen in time. One I visited was the same as it was in 1959. I love walking into a place and feeling like I’ve stepped back in time,” he says.

Warren says he thinks it’s important to document what is disappearing.

“I guess that’s basically what I’m doing. There’s a foundry I visited a few times in Sunshine. It’s a third-generation factory and stacked high with patterns and moulds,” he says.

“They can’t understand what I see in the place, but I see it as a one-of-a-kind. I look at the small, arcane working conditions and I know I wouldn’t last until morning tea working there, but to me it is beautiful; visually stunning.

“It’s the end of an era and of its type and it has soul and beauty. I consider people working in those conditions as heroic.”

Take a look at Warren Kirk’s photos on his Westographer Flickr page.

Laurie Nowell

AMES Senior Journalist