Solving the population projection riddle

Statisticians in the US have developed the first model to accurately predict the way migration affects population projections.

The researchers, at the University of Washington, have reduced the uncertainty factor of migration in population estimates – a difficult issue that has been plaguing demographers for decades.

Their model, published in the ‘Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences’, also provides population projections for all regions worldwide — and challenges the existing predictions for some, particularly the United States and Germany.

“It turns out that for quite a few countries, migration is the single biggest source of uncertainty for population projections,” said chief researcher and Professor of Statistics and Sociology Adrian Raftery.

For the first time, the researchers used a “probabilistic” model that draws on migration rates in each country and worldwide over the past 65 years, along with patterns of fertility and mortality, to project population around the world.

They predicted that the US population has a 10 per cent chance of exceeding 610 million over the next 85 years – nearly double the current population – when migration is factored in, versus a projected high of 510 million if it isn’t.

While that likelihood is small, it has large ramifications, said co-author Jonathan Azose.

“If you think about planning for social welfare programs, sometimes the biggest issues arise when these unexpected events occur,” he said.

“Countries need to be prepared for the possibility.”

“Countries need to be prepared for the possibility.”

But migration is a difficult force to predict, driven by factors ranging from war to economic crises, employment opportunity, family dynamics and even migration policy, which can themselves be difficult – if not impossible – to foresee.

To arrive at their projections, the researchers looked at past migration patterns in each country to determine a range of probability for future outcomes, reasoning that recent history creates an environment that is likely to create similar migration patterns going forward.

“A lot of the influences that have produced migration levels in the recent past are baked in and likely to continue to play a role in the future,” Prof. Raftery said.

“It’s almost impossible to tease out all factors, but using current levels of migration, this is the best we can do.”

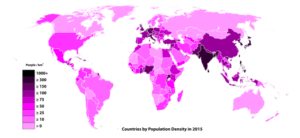

The researchers then incorporated global migration patterns to build a statistical model and make population projections for each country. Some regional patterns emerged.

Smaller European countries that have experienced broad swings in migration over the past half-century are more likely to be impacted by migration uncertainty than countries like India and China, where migration rates are smaller relative to their large populations.

The findings were most striking for Germany, whose bureau of statistics has called population decline “inevitable” as the country’s populace ages.

But the model predicts that when migration is factored in, Germany’s population decline could be offset by the arrival of more than 1 million immigrants every five years for most of the next century.

The data in the study was collected before the influx of more than 965,000 migrants and refugees into the country in 2015, so the near-term difference could be even more dramatic.

“Our model could change the perception of the future of Germany from a country that goes into decline for the rest of the century to one that may not, if its policy of accepting migrants continues,” Prof. Raftery said.

The researchers also predicted that France and the United Kingdom are likely to have bigger populations than Germany by 2060, given both countries’ higher fertility rates.

The researchers’ model contrasts with the traditional “deterministic” approach that projects current mortality, fertility and migration rates into the future to estimate population size. But migration rates vary considerably in many countries and fluctuate over time, Prof. Raftery said, making for unreliable estimates.

Leaving migration out of the equation can lead to long-term challenges for nations in planning for social programs, the researchers said.

Many European countries are cutting education funding in anticipation of declines in school-aged populations, they said, which could lead to school closures and fewer trained teachers.

“If the school-age population turns out to be larger than the space allocated for them, there can be huge costs associated with opening or reopening schools and finding teachers to staff them,” he said.

“International migration, and especially refugee migration, typically includes large numbers of school-aged children,” Prof. Raftery said.

Laurie Nowell

AMES Australia Senior Journalist