Melbourne’s secret history of cultural diversity

If you think, as most people do, that Melbourne’s vibrant brand of multiculturalism began in the 1950s with the arrival of Italian and Greek migrants fleeing post-war austerity in Europe – you’d be wrong.

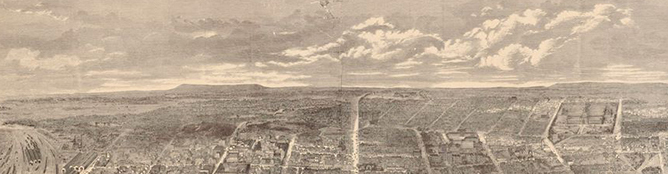

Long before the Italians brought their espresso machines and the Greeks their souvlaki and the Orthodox Church, Melbourne was a polyglot city; home to thousands of residents from across the globe.

As far back as the 1890s, a walk through the lanes and streets of what is now the inner city would have exposed one to a diverse spectrum of languages including several Chinese dialects, French, German, Norwegian, Hindi, Pashtu and Arabic.

Now, new research has thrown light on how communication and the translation of languages played a key role in early the life of colonial Melbourne and has revealed for the first time the rich diversity of language and culture which existed.

Now, new research has thrown light on how communication and the translation of languages played a key role in early the life of colonial Melbourne and has revealed for the first time the rich diversity of language and culture which existed.

La Trobe University researcher Dr Nadia Rhook spent six years researching court trials where an interpreter was employed unearthing a surprising picture of linguistic difference and diversity that resonate with current debates around migration and refugees.

“The project mapped the language-scape of Melbourne in the 1890s,” Dr Rhook said.

“The findings are still relevant today because of the dominance of English in social and economic life and in the courts,” she said.

Dr Rhook says her research shows Melbourne has always been a polygot city with a fluidity of language as new waves of migrants arrived.

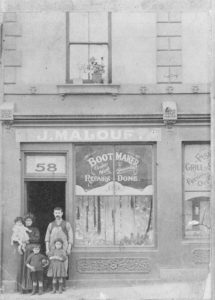

“Melbourne had a deep linguistic diversity back in the 1890s. Most people know about the Chinese who came here but there were also Syrians from current-day Labanon, Indians and Afghans,” she said.

“I was surprised to find a substantial number of Indians living in Melbourne. But until lately this community has not been memorialised in the city in any physical way.

“The Indian migrants were obviously British subjects in the time of the Empire and they had rights and stood up for them,” she said.

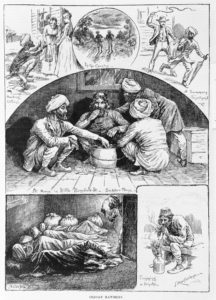

“The prominent Bangalore-trained masseur Teepoo Hall was particularly vocal in the early years of the White Australia Policy.

“The prominent Bangalore-trained masseur Teepoo Hall was particularly vocal in the early years of the White Australia Policy.

“But Melbourne’s historical diversity seems to have been whitewashed,” Dr Rhook said.

She said the interpreters who worked with Melbourne’s diverse migrant communities became celebrities in their day.

“These men were well connected to the communities and to government and so were influential. Their status shows the power of language especially in an imperial setting which encompassed lands across the globe,” Dr Rhook said.

One of the interpreters was Charles Hodge, a failed goldminer who turned to interpreting on Victoria’s goldfields.

“Hodge moved to Melbourne and became an ally of the Chinese community. He was the long-standing interpreter in court cases involving Chinese.” Dr Rhook said.

“He was made a ‘mandarin’ by the Chinese Government and was presented with the full set of regalia. He marched proudly up Swanston Street with the Chinese community at the inception of Federation. He was perhaps Australia’s first celebrity migrant advocate,” Dr Rhook said.

Dr Rhook’s work is encapsulated in an exhibition that went on display at the City Library last month.

Titled Moving Tongues: language and migration in 1890s Melbourne, it tells part of the story of the colonisation of Kulin lands which saw migrants from far flung corners of the globe settle in Melbourne.

While diverse languages were spoken in Melbourne, the corridors of power, were dominated by English-speaking men, and a proposed Immigration Restriction Act threatened to reduce the city’s linguistic diversity.

While diverse languages were spoken in Melbourne, the corridors of power, were dominated by English-speaking men, and a proposed Immigration Restriction Act threatened to reduce the city’s linguistic diversity.

The exhibition tells the story of the ultimately tragic case of young Norwegian housekeeper Louisa Fritz who was assaulted by her employer Theodore Ulstein.

Louisa had migrated from Norway in the early 1890s. Louisa came under intense scrutiny in the ensuing trial because of her language ability. Months later Louisa and her mother were charged of the crime of attempting suicide.

There is also a depiction of the presence of Syrians and ‘British Hindoos’ and their sleeping arrangements in the terraced shops of Little Lonsdale and Exhibition Streets; as well as the alliances they formed with indigenous people.

Dr Rhook has conducted walking tours and is now writing a book based on her research.

“It’s so exciting to share stories about the historical depth of multilingualism in Melbourne. English may have become an important ‘lingua franca’ but Melbourne has always been a multilingual city, and there are so many histories of communication, translation and linguistic justice that have lessons for today,” she said.

Laurie Nowell

AMES Australia Senior Journalist