Rethinking the history of prehistoric migration

Conventional history tells us that Europeans went from hunter-gatherers to farmers because of an influx of migrants from the Middle East.

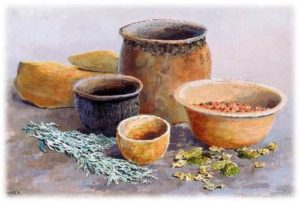

Life in Europe was revolutionized during the late Stone Age when technologies such as ceramics, the farming of grains, cultivated cereals and domesticated livestock arrived.

This cluster of technologies – that changed the way Europeans lived, bringing about the end of hunter-gatherer lifestyles and replacing them with a farming way of life – is known as the ‘Neolithic Package’.

But a new study suggests the process was much more complicated.

But a new study suggests the process was much more complicated.

Study of ancient DNA suggests that this Neolithic package was spread to and through Central and Western Europe by the migration of farmers from the Levant and Anatolia. These farmers interbred with and ultimately replaced Europe’s hunter-gatherers.

Published in the journal Current Biology, the latest study suggests that migration was not a ‘universal driver’ for the spread of farming through Europe.

Although archaeology shows that the technologies of the Neolithic Package did reach the Baltic region, the genetics of the populations there remained the same as those of the hunter-gatherers throughout the Neolithic.

“Almost all ancient DNA research up to now has suggested that technologies such as agriculture spread through people migrating and settling in new areas” said researcher Andrea Manica of Cambridge University.

“However, in the Baltic, we find a very different picture, as there are no genetic traces of the farmers from the Levant and Anatolia who transmitted agriculture across the rest of Europe,” Dr Manica said.

“The findings suggest that indigenous hunter-gatherers adopted Neolithic ways of life through trade and contact, rather than being settled by external communities. Migrations are not the only model for technology acquisition in European prehistory,” he said.

The team extracted ancient DNA from a number of remains discovered in Latvia and Ukraine dating to between 5,000 and 8,000 years old. The remains spanned the Neolithic period, and the transition from a hunter-gatherer way of life to one based on food production.

The results shed new light on the spread of Indo-European languages. Although showing no influence from Levantine farmers, one of the Latvian genomes did show signs of an external influence which the scientists believe could be from the Pontic Steppe in the East.

Co-researcher Eppie Jones, of Trinity College Dublin said there were two major theories on the spread of Indo-European languages, the most widely spoken language family in the world.

One is that they came from the Anatolia with the agriculturalists; another that they developed in the Steppes and spread at the start of the Bronze Age.

“That we see no farmer-related genetic input, yet we do find this Steppe-related component, suggests that at least the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European language family originated in the Steppe grasslands of the East, which would bring later migrations of Bronze Age horse riders,” Dr Jones said.

The study suggests the arrival of the Neolithic Package to the Baltic region was a much more gradual process than elsewhere in Europe, facilitated by trade networks rather than rapid migration and interbreeding.

“It seems the hunter-gatherers of the Baltic likely acquired bits of the Neolithic package slowly over time through a ‘cultural diffusion’ of communication and trade, as there is no sign of the migratory wave that brought farming to the rest of Europe during this time,” Dr Manica said.

“The Baltic hunter-gatherer genome remains remarkably untouched until the great migrations of the Bronze Age sweep in from the East,” he said.

Laurie Nowell

AMES Australia Senior Journalist