Is the welcome for Syrian refugees wearing thin?

The welcome neighbouring countries gave to Syrian refugees may be starting to wear thin as the conflict enters its eight year.

The welcome neighbouring countries gave to Syrian refugees may be starting to wear thin as the conflict enters its eight year.

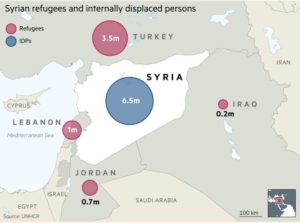

Aid agencies are reporting growing resentment towards the millions of Syrians who have fled the seven-year civil war has been growing across Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan, the countries hosting the largest number of refugees.

They have warned that despite continued bloodshed in Syria, there is growing political pressure in host countries for them to return home.

“There’s an anti-refugee backlash that has been steadily growing,” says Daniel Gorevan of the Norwegian Refugee Council.

“There has been an increase in discussion about the return of refugees that doesn’t match what is happening on the ground in Syria.”

Turkey was lauded internationally for opening its doors to 3.5m Syrians fleeing the war. But social tensions are rising.

Now, 75 per cent of Turkish citizens believed Turkish and Syrian communities could not live in peace, according to a recent study by Istanbul’s Bilgi University.

Almost two-thirds of respondents — including 45 per cent of Erdogan voters — said the government’s policies towards Syrians were wrong.

Public hostility has shaped the political rhetoric.

Less than two years ago, President Erdogan promised Turkish citizenship for refugees. Now he says that one of the aims of the Turkish military operation in the Syrian enclave of Afrin is to provide a way for them to return home.

This is despite most of Turkey’s refugees hailing from elsewhere in Syria.

We want our refugee brothers and sisters to return to their own land, their own homes. We cannot keep 3.5 million people here for ever,” President Erdogan said last month.

While refugees bring economic benefits through spending money, starting businesses and providing cheap labour, host governments in the region have spent billions supporting them.

In Lebanon, where one in four people is a Syrian refugee, officials say the displacement crisis has cost the country more than $US20bn.

In Jordan, authorities say the cost is as high as $US10bn.

The Turkish government has said it has spent $30bn.

Despite the shift in official statements, Turkish officials continue to work behind the scenes on improving refugees’ access to education and health services.

But in Lebanon, Syrian refuges say the authorities are making life more difficult for them.

There are other signs that the Syrians’ welcome in the region is running out.

Jordan has left almost 50,000 refugees languishing in a rudimentary camp near Syria’s southern border, citing security concerns as the reason for their refusal to let them enter.

Turkey’s border has also been closed since 2015 to the majority of Syrians.

In both countries, human rights groups warn of growing forced deportations.

As Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad gains the upper hand in the war and the recapturing of territory from the extremist group ISIS, there had been an expectation that the conflict would wind down.

But Syria’s internecine war has, in some areas, entered its bloodiest phase yet.

Experts say that the pressure for the premature return of refugees has been exacerbated by the failure of other nations to step up.

EU member states host about a million Syrians between them — with two-thirds of them in Germany and Sweden — compared with 5.2 million across Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon.

The number being resettled in countries outside the region has plunged, driven by a western backlash and President Donald Trump’s decision to slash the US refugee quota.

Laurie Nowell

AMES Australia Senior Journalist