A century and a half of contestation over Chinese migration in Queensland

The 5th of May is the anniversary of an anti-Chinese riot, which has not been acknowledged with a title and typically passes unobserved by residents of South-East Queensland.

With over 95,000 Queenslanders identifying as Chinese diaspora in 2021, it is difficult to believe that on that night in 1888 “none of the Chinese premises in [Brisbane’s central business district] were left unvisited” by a violent mob of around 2000 settlers.

When Ms Sandy Tsang, a teacher in the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP), was asked whether Chinese migrants to Brisbane felt safe, her reply was, “I believe so”.

When Ms Sandy Tsang, a teacher in the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP), was asked whether Chinese migrants to Brisbane felt safe, her reply was, “I believe so”.

“A significant number of my students arrive here seeking family reunification,” she said.

“[They live] predominately on the southern side, with a concentration in areas like Sunnybank, Rochedale, Calamvale, and Kuraby,” said Ms Tsang.

She has been teaching English to migrants and refugees for 43 years, beginning with Vietnamese refugees in Hong Kong.

Ms Tsang migrated to Australia in 1997, when Hong Kong was return to the Chinese after 99-year lease by the British, which was negotiated at the conclusion of the Opium Wars.

Sunnybank is regarded by some historians as an authentic alternative to the Chinatown of the Fortitude Valley.

It was arguably constructed as a tourist attraction by the Brisbane City Council for World Expo88, in response to the noted absence of one during the 1986 Commonwealth Games.

Chinatowns, worldwide, are enclaves which establish physical infrastructure over long periods for the protection of their members.

The 5th of May 1888 was the counting day for an election, in which both Liberal and National parties campaigned for the prevention of the Chinese migration.

Its riot also occurred in the wake of the Aghan Affair, which saw 268 Chinese passengers on the eponymously named steamer prevented from disembarking in Sydney by approximately 5000 protestors.

Its riot also occurred in the wake of the Aghan Affair, which saw 268 Chinese passengers on the eponymously named steamer prevented from disembarking in Sydney by approximately 5000 protestors.

It has been argued that the Chinese in South-East Queensland deliberately dispersed after Brisbane’s original Chinatown was attacked, out of concerns that congregating as a community might, again, attract negative attention.

Whilst burgeoning in the 1980s, the naissance of Sunnybank’s Chinese community appears to have been in market gardening near the present-day Bannon railway station.

A report on a flood in 1908 published by The Week made mention of the Chinese market gardeners, a year shy of the Brisbane Markets banning their produce.

This exclusion reflected a sustained campaign by the Anti-Chinese League in South-East Queensland, a victory admired by lobbyists around Australia.

Whilst many of their compatriots appear to have relocated as a consequence, some persisted, like Ah Loui who died in the 1930s.

This community endured the restriction of Chinese immigration by the White Australia Policy between the 1900s and the 1970s and a resurgence of xenophobia driven by Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party in the 1990s.

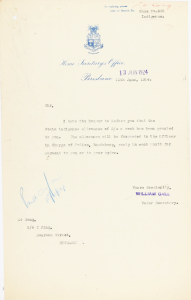

However, contrary to the vehement racism proliferated by publications like Queensland Figaro, Queensland State Archives records would suggest some value may have been attributed towards this hard-working group of migrants.

For example, many elderly Chinese were amongst the recipients of indigence payments when they commenced at the turn of the century in Queensland.

Few had the opportunity to start families in Australia owing to the disproportionately low number of women in the Chinese population.

Only eight Chinese women appeared on Brisbane’s Aliens List in 1916.

The allowance was offered to some settlers in lieu of being sent to the Dunwich Benevolent Asylum, where the deserving poor were sent to die outside of the public eye.

There, an Alien’s Ward housed Chinese diaspora from a diversity of regions, including Macao and Hong Kong.

The residents also represented a plethora of professions, which they took up after fulfilling their contractual obligations as part of the credit-ticket system.

A notably large contingent originated from Fujian, including the pastural workers who have become known as the Amoy Shepherds.

This goodwill from the government extends to the present day, with “complimentary interpretation services at all government offices and access to free English classes” among the kinds of support Ms Tsang recalled offhand.

“To my students, language is the biggest hurdle,” Ms Tsang said.

“This challenge becomes pronounced… if they experience a breakdown in relationships with their family in Australia.”

In the 2020s, Sunnybank could be considered an eclectic residential and commercial centre primarily owned and operated by Asian migrants.

Many of the hospitality and retail outlets have Mandarin, if not Cantonese, speaking staff.

However, they appear welcoming of all customers irrespective of the ancestry with which they might identify.