Applying physics to the refugee problem

The ostensibly irrelevant disciplines of physics and mathematics have been applied to Australia’s interminable and divisive asylum seeker issue with some surprising results.

Prompted by immigration minister Peter Dutton’s recent comment about “innumerate” asylum seekers arriving in Australia, University of Queensland Quantum Physicist, Thomas Stace decided to bring some numeracy expertise to the problem.

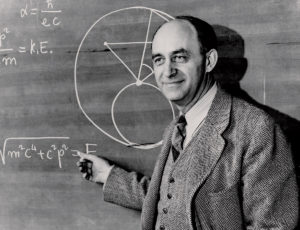

Writing in the journal Phys-Org and for The Conversation, Professor Stace described how he enlisted the example of one of 1938 Nobel prize-winning physicist Enrico Fermi’s famous ‘problems’.

“Fermi was renowned for his back-of-the-envelope numerical estimates, having calculated the yield of the first atomic bomb blast based on the distance its shock wave carried some shredded tissue paper he had brought to the Trinity test,” Prof. Stace wrote.

Enrico Fermi

He said Fermi was also known for his ‘Fermi problems’, with which he tested his students.

“It’s an approach that can be applied to the current asylum seeker discussion,” Prof. Stace wrote.

“One Fermi problem that has been handed down to generations of physicists asks: ‘how many piano tuners work in Chicago?’.”

The question has not much to do with physics but arriving at an answer requires a skill valuable to physicists: the ability to make estimates from reasonably assumed numbers.

Prof. Stace described a typical response to the piano problem:

There were about 500,000 households in Chicago, of which about a fifth have a piano, so there are about 100,000 pianos.

If a typical piano needs tuning every two years, 50,000 pianos need tuning per year.

If it takes a piano tuner three hours to tune a piano, a full-time worker (working 2,000 hours a year) can tune about 660 pianos in a year.

So there’s enough work for about 75 piano tuners in Chicago.

“We can apply the same approach to the increasingly divisive issue of asylum seeker policy,” Prof. Stace wrote.

“In Australia, and in Europe, the debate has polarised into two camps: one driven by compassion for individuals escaping dire circumstances; the other by the need to regulate migration across national borders,” he said.

“The ‘compassion’ side recognises our common humanity, and our existing commitments to provide asylum to those escaping persecution.

“The ‘controlled migration’ side recognises that there are limits to the capacity for any nation to absorb a sudden, large influx of immigrants.

“In this confused situation, Fermi, who himself immigrated to the United States to escape anti-semitic laws in Mussolini’s Italy, might well ask:

“’How many refugees can the wealthy nations of the world accommodate?” Prof. Stace wrote.

“The question, and its answer, is about capacity, not political will. But given this proviso, if the answer is ‘fewer than there are people in need’, then there is genuinely no solution to be found. On the other hand, if the answer is ‘more than there are in need’, then there is capacity, at least.

“So what’s the answer? The first part is straightforward: the number of international asylum applications each year fluctuates between one and two million.

“The debatable part of the calculation requires an estimate of the number of immigrants a nation can take each year.

“To give some Australian context, there are around 190,000 immigrants coming to Australia each year under our migrant program, and between 6,000 and 12,000 refugees arriving annually under our refugee resettlement program.

“My estimate is that a wealthy nation can comfortably accommodate refugees up to about 0.2 per cent of its population per year.

“Why 0.2 per cent? Why not 1 per cent? Well, after ten years at 1 per cent annual intake, 10 per cent of the population would be a first-generation refugee migrant.

“This is a number that will start to be felt as a significant demographic shift, with the potential for political backlash.

“At 0.2 per cent annual intake, it would take 50 years to reach this level. This is plenty of time for both immigrants and social structures to adapt and integrate.

“For Australia, the current population is about 24 million so a 0.2 per cent annual intake equals about 48,000 refugee places that we could comfortably resettle per year.

“This is lower than our skilled migration program admits, and larger than the proposed refugee and humanitarian quotas of the Liberal Party (18,750) and the Labor Party (27,000). The Greens have a more expansive policy (50,000).

“Indeed, this is the root of the political problem that some have described as ‘wicked’: the global demand for asylum dwarfs all of these numbers, so Australian politicians cannot unilaterally fix the issue.

“But resettlement should be shared across the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) representing wealthy nations that can afford to carry the load.

“The total population of the OECD nations is more than a billion. A resettlement rate of 0.2 per cent across the OECD equals more than two million refugee places per year. This is larger than the typical number of annual asylum applications.

“So, Fermi has given us an answer: there is international capacity to distribute the flow of asylum seekers across the wealthy countries of the world.

“An orderly and politically manageable process to achieve this requires international coordination. This is a diplomatic problem that Fermi can’t answer.

“But with political will, it has been solved in earlier decades of conflict-driven migration,” Prof. Stace wrote.