Book probes lived experience of statelessness

In the 2004 film ‘The Terminal’, Tom hanks plays an Eastern European man stuck in New York’s John F Kennedy Airport when he is denied entry to the US but cannot return home because a military coup in his homeland rendered him stateless.

In the 2004 film ‘The Terminal’, Tom hanks plays an Eastern European man stuck in New York’s John F Kennedy Airport when he is denied entry to the US but cannot return home because a military coup in his homeland rendered him stateless.

About twenty years earlier, Japanese anthropologist Professor Lara Tienshi Chen experienced the same thing in real life at an airport in Tokyo.

The incident led her to a life-long study of statelessness. She has also found the Statelessness Network, a not-for-profit organisation which supports stateless individuals and groups.

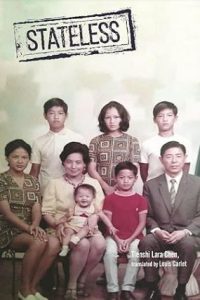

And she has written a book titled ‘Stateless, My Autoethnography’, which describes her search for identity as the daughter of Chinese parents who was born in Japan.

She spoke of her journey through a lived experience of statelessness in a recent webinar, hosted by the Peter McMullin Centre on Statelessness at Melbourne Law School.

“My parents were forced to move to Taiwan after the communist takeover of mainland China. My father’s family had been landlords and my mother’s father was a general in the republican army,” Prof Chen said.

“My father moved to Japan in the 1960s and settled among the Chinese community in Yokohama with mother joining him there later. I was born in Yokohama in 1962.”

But Japan’s 1972 termination of diplomatic ties with the Republic of China (Taiwan) left 9,200 Chinese residents stateless.

Prof Chen was one of them but didn’t realise that until years later.

Prof Chen was one of them but didn’t realise that until years later.

“When I was 21, we went on a trip to the Philippines and on the way back, my mum said: ‘why don’t we stopover in Taiwan?’

“My parents were able to enter Taiwan easily because they had been born there, but at the immigration counter an official said that my passport was not recognised and that I needed a visa.

“I went back to Japan and used my documents to try to enter the country but an official at the airport again said: ‘you cannot enter’.

“I asked why because I had been born and raised in Japan and they said: ‘your visa has expired’.

“I was twenty-one, I found myself stuck at the border between two familiar countries, unable to enter either. I had never felt my statelessness so keenly.

“At that point I realised I was stateless. And from then on, my certificate of alien registration labelled me stateless.

“When I went to the bank to open an account or tried to rent an apartment, people were reluctant to help me,” Prof Chen said.

She said she began to question her identity.

“I started to question who I was and where I belonged. I suffered an identity crisis.”

Prof Chen said many of the 9,200 stateless Chinese, returned to China or migrated elsewhere and a few years later, the number had dropped to 2,700.

“I remained stateless because my father was reluctant to change his nationality to the People’s Republic China because of what had happened to his family and my mother refused to become a Japanese citizen because of memories of World War II,” she said.

“I was 30 before I became a Japanese citizen. It was difficult to get a job in Japan as a stateless person. That’s when I decided to research statelessness.”

After completing her degree, Prof Chen went on study a master’s degree in Hong Kong and a PhD in the US.

She has since become a leading international advocate for stateless people and an academic at Japan’s Waseda University.

“I still feel stateless. Not many people see me as Japanese in daily life,” Prof Chen said.

Her book was turned into a television documentary, and she has advocated for stateless people in the media.

The book includes studies of stateless communities and individuals around Asia and analyses the idea of citizenship by exposing the hidden everyday stories and lived experiences of people who have no legal ties to any nation state.

“My work has been a search for answers to questions about ‘where is home?’ and ‘where do we belong?’

“Should this be based on citizenship? What about cultural identity, or local identity in which where you live is your identity?

“To be stateless is another identity and maybe everyone is a ‘rainbow person’ with multiple identities.

“I think the term ‘rainbow’ is a metaphor for stateless people. It means stateless people have the confidence to a human being and global citizen,” Prof Chen said.

‘Stateless’, by Lara Tienshi Chen, published by NUS Press, is available online.