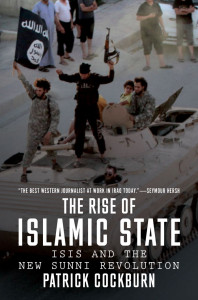

Book Review: The Rise of Islamic State

The Rise of Islamic State is published by Verso Books.

It’s easy to think of the rise of ISIS as a sudden explosive phenomenon when you look at the mainstream media coverage.

The group only really received coverage when it began to take important towns and oil fields.

But a new book, The Rise of Islamic State, by Patrick Cockburn, a journalist with the UK’s Independent newspaper, presents a picture of ISIS’s progression from fringe group to popular Sunni extremist group set against a background of intriguing by the US, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Rather than a sudden, freak event, Cockburn says the rise of ISIS was logical and predictable.

He says the wars in the Middle East over the years have become more and more brutal and violent. It started with the mujahedeen in Afghanistan, aided and abetted by the US, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan’s ISI.

After successfully getting rid of Soviet forces, those “freedom fighters” morphed into the Taliban, where the ideology of al-Qaeda grew its protected roots, Cockburn says.

He says that when Iraq was attacked by the US in 2003, al-Qaeda found a new place to spread its influence where it had not been before. At first, it found support with the disenfranchised Sunni tribes, later minimized by the “Awakening”—the US big dollar effort to buy out the Sunni leaders.

The war in Iraq left in its wake a highly unstable state essentially divided into three parts: Kurds in the northeast, Sunnis in the west, and the Shia in the south.

The fighting that has been waged since the US withdrawal has attracted little attention among western news networks.

Overlaid on this, says Cockburn, is the new and increasingly fierce fighting in the civil war in Syria, pitting the Assad government, backed by Russia, against a web of opposition groups backed by the US and its allies.

The combination of disaffected Sunnis – many former military personnel, many affected by the Sunni-Shia fighting – and well supplied and trained fundamentalist Islamic groups—again with US and Saudi direction – in Syria coalesced into ISIS, a new and more ruthless and efficient fighting organisation.

The historical precedents, Cockburn says, indicate that it is unlikely the “Sunnis will rise up in opposition to ISIS and its caliphate. A new and terrifying state has been born that will not easily disappear”.

Cockburn says the US must take much of the blame for this sequence of events, much more so than Iraq and Syria as standalone countries, or Turkey as an anti-Kurd, quasi-ISIS supporter.

“There was always something fantastical about the US and its Western allies teaming up with the theocratic Sunni absolute monarchies of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf to spread democracy and enhance human rights in Syria, Iraq, and Libya,” Cockburn says.

“ISIS is the child of war….It was the US, Europe, and their regional allies in Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait, and [UAE] that created conditions for the rise of ISIS,” he says.

Implicit in Cockburn’s analysis is that if ISIS is the child of war, then the US is one of its parents. The Sunni resurgence in Iraq was not an overnight sensation, but had a gestation period of several years.

The book makes depressing reading as it assesses the ineptitude of the west in combating the rise of the influence of ISIS.

Cockburn makes an argument that says we are now in the early stages of a new phase of Islamic militancy.

The death of Osama bin Laden in May 2011, and the outbreak of revolts across much of the Arab world, marked the end of a cycle that had commenced with the 9/11 attacks.

This cycle had peaked in terms of violence around 2005 and then subsided towards the end of the decade as militant groups found their geographic and ideological space squeezed.

Cockburn says it now looks like we are on another upswing with vast tracts of desert and dozens of towns under extremist authority in the Middle East and a new energy flowing through the myriad networks that make up the movement as a whole.

So, if Cockburn could see what was happening, how did western security officials, politicians and analysts not see it.

Probably, Cockburn argues, because western policymakers have shown little real action or even will in dealing with the conflict in Syria or the disintegration of peace in Iraq.

Of all the mistakes Cockburn says were made by both the rebels and their foreign backers since 2011, it was the belief that President Assad was going to be swiftly defeated that was the most serious.

The major theme that emerges from Cockburn’s book is the role of nation states in the whole tragic saga. Islamic militant groups are not usually described as states but The Rise of Islamic State argues otherwise.

Cockburn’s thesis, ultimately, is that everybody now seems to have some kind of involvement in this fight, which may have killed more than 200,000 people, but no one has any ideas about how it might be brought to an end.

The Rise of Islamic State, by Patrick Cockburn, is published by Verso Books.

Laurie Nowell

AMES Senior Journalist