Book review – The Unsettling of Europe Nothing new about Europe’s migrant crisis

The high level of migration into Europe in recent years has been described by some politicians as ‘apocalyptic’.

And while it’s true that numbers of people displaced across the globe for reasons of conflict and persecution are at an all-time high, a new book seeks to apply some context to the situation.

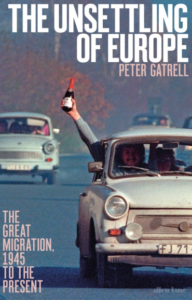

Professor Peter Gatrell’s latest book ‘The Unsettling of Europe’ is a detailed and sensitive guide to the violent uprootings and unremarkable journeys that shaped between 1945 and the present day.

Professor Peter Gatrell’s latest book ‘The Unsettling of Europe’ is a detailed and sensitive guide to the violent uprootings and unremarkable journeys that shaped between 1945 and the present day.

It speaks to how for decades Europe has alternately recruited and punished migrants and examines why so many people find it hard to them as fellow human beings.

It describes how migrants are central to modern Europe’s experience, whether trying to escape danger, to find a better life or as a result of deliberate policy, whether moving from the countryside to the city, or between countries, or from outside the continent altogether.

The book brings all of these stories together into one place, creating a compelling narrative bookended by two difficult periods: the great convulsions following the fall of the Third Reich and the mass attempts in the 2010s by migrants to cross the Mediterranean into Europe.

Perhaps its major contribution is to remind us that high levels of displacement and mobility have actually been fairly routine in Europe in relatively recent times.

This new history of the continent of Europe charts the ever-changing arguments about the desirability or otherwise of migrants and their central role in Europe’s post-was prosperity.

Prof Gatrell gives fascinating accounts on the giant movements of millions, such as the epic waves of German migration. He also focuses on smaller groups, such as the Karelians, Armenians, Moluccans or Ugandan Asians who settled in Europe.

The book makes the reader acutely aware of and evokes a sense of understanding many extraordinary journeys taken by countless individuals in pursuit of safety, work or dignity over the decades.

Prof Gatrell, who teaches History at Manchester University, explores the notion of migration in its broadest sense and demonstrates the insanity and impossibility of distilling issues around international mobility down to a single ‘migrant crisis’.

He points out that as well as post-war traumas of expulsion and resettlement, there were efforts by western nations to recruit labour from overseas to rebuild their shattered economies; thus modern, skilled migration became a thing.

Interestingly, Prof Gatrell identifies three strands of migrants in the post-war year; and some of the the analysis stands true largely today.

There were those forcibly displaced either by violence or deliberate government policy; there were ‘returning’ groups – mostly people who had managed the colonies of various European nations; and, there were was the labour force deliberately recruited by governments looking for economic growth.

The one thing all these groups had in common was the hostility they faced from host populations.

The same myths that perpetuated after WWII – that migrants rip off the welfare system, take our jobs and bring crime and disease – are still around.

The book, admirably, give voice to migrants themselves and what emerges is that many of them success in negotiating the tangle of stereotypes, prejudice and barriers to find their places in a new society.

But one conclusion is that the negative generalised themes and stereotypes continue today in spite of hard evidence to the contrary.

But the book makes significant contribution to dismantling the tired clichés about migrants and it puts in context the current migration issue in Europe by postulating that European modernity began with massive migratory undertakings.

These were the movement of European people to other continents as traders and ultimately rulers and the movement of peoples out of Africa through the Atlantic slave trade.

Prof Gatrell concludes his study with the assertion that what the populations of host countries need to make them more welcoming of migrants are the opportunity to engage at a local level with the newcomers; and, the continuation of their safe and stable environments with the continued provision of just systems of law and welfare that are not impacted by an influx of migrants.

The book is a welcome sober and sensible look a migration – both its problems and its benefits – in a post-truth age of fake news and dog whistle politics.