Desperate Venezuelans migrants opting for dangerous sea route

As economic and social conditions continue to deteriorate in Venezuela, desperate would be migrants have found a new and dangerous maritime route out of the country.

Increasingly desperate residents of the country’s Caribbean coast are choosing a dangerous sea crossing as they try to find new lives.

Just 24 kilometres away, Trinidad and Tobago has become a key destination for some of the millions of Venezuelans eager to escape the country’s economic meltdown and humanitarian crisis.

Just 24 kilometres away, Trinidad and Tobago has become a key destination for some of the millions of Venezuelans eager to escape the country’s economic meltdown and humanitarian crisis.

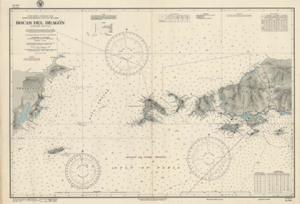

The route, known as Bocas del Dragón (Mouths of the Dragon) is a dangerous waterway notorious for human smuggling, narco-trafficking, shipwrecks, and even piracy.

Shipwrecks have increased in recent years; three boats were reported missing in 2019, with a total of at least 80 people on board.

Last December, another vessel sank in choppy waters, drowning at least 36 Venezuelans, including several children – the second disaster of the year.

And just last month, a boat carrying 24 Venezuelans bound for Trinidad and Tobago capsized off the same coast, leaving at least 17 people dead or presumed dead.

Many of the escapees are in poor health, suffering mild malnutrition, or have endured extreme poverty for years.

And as Venezuela buckles under a second wave of COVID-19 infections that have resulted in intense lockdowns throughout the country, more Venezuelans are expected to opt for the sea journey.

Local reports say many of the migrants are drawn by the tourism industries in the Caribbean islands for work opportunities.

A recent UN report says 2.5 million Venezuelans face severe food insecurity, and earlier reports estimate a third of the population needs food assistance.

According to the UN, more than 5.5 million Venezuelans have left the country since the start of the country’s crisis.

Venezuelans have faced a worsening economic crisis and humanitarian emergency since 2014, and the country’s northern coasts have been particularly hard hit due to lack of tourism and the impact of organised crime on small-scale fishing.

The most recent study by Venezuela’s National Institute of Statistics (INE), released in 2016, reported that 52 per cent of the northern province of Sucre’s nearly one million residents lived in poverty, and 20 percent experienced extreme poverty.

The unemployment rate stood at 42 percent. Those numbers are likely to have risen a lot since, as Venezuela’s overall situation has rapidly declined, with 5,500 percent inflation forecast for 2021.

According to some estimates, there are already around 24,000 Venezuelan migrants in Trinidad and Tobago, which has a population of nearly 1.4 million people.

That number is likely to be underestimated because most migrants enter the country by irregular means and never have interactions with government systems or officials.

A 2019 report by Refugees International put the number of Venezuelans on the island at 40,000 and quickly growing – which would give the country the highest per capita Venezuelan population in the Caribbean.

To be granted asylum, migrants must prove they will face credible risk in their home country. The government of Trinidad and Tobago considers all other Venezuelans “economic migrants”, who are not protected under Trinidadian law.