EU elections see a drift to the right

Europe’s nationalist political movements have gained some ground in the recent EU Parliament elections and now are expected to try to unite behind the common goals of anti-migration and nationalism.

But observers say they face an uphill battle to usurp the pro-EU policies of the majority of Europe’s political parties.

to usurp the pro-EU policies of the majority of Europe’s political parties.

More than 400 million Europeans from 28 countries voted for a new five-year term of the European Parliament.

The issue of migration was less prominent than in the past, but the results of these elections will have ramifications for refugees and migrants, both at the national and the EU level.

Heading the nationalist challenge is Italy’s Matteo Salvini, whose ‘Liga’ party has become a leading eurosceptic force and wants to bring together like-minded parties scattered across several groups in the European Union legislature.

The Italian Deputy Prime Minister has said he wants to form a bloc of 150 lawmakers and had discussed the matter with Marine Le Pen’s National Rally in France, Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party in Britain and Prime Minister Viktor Orban in Hungary.

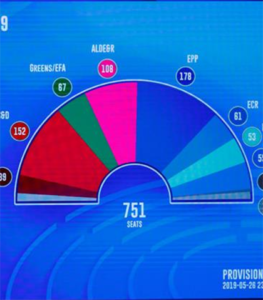

Provisional results show that more than 170 seats, or 23 per cent of the 751-member assembly, went to parties that sat in eurosceptic groups in the last parliament.

That was up from 20 per cent, a smaller gain than some had expected for the far-right, and still leaving left-wing pro-European parties with a firm majority.

The push for a nationalist bloc is complicated by differences on big issues like asylum and relations with Moscow.

At least, though, one of the three groupings in which they are currently divided looks set to disappear.

After poor results by most of its members, the Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD) group – led by the UK Independence Party (UKIP) and Italy’s anti-establishment 5-Star Movement – will struggle to reach the threshold of seven national parties necessary to form a group in the EU assembly.

In another possible boost to Salvini’s plan, Poland’s ruling nationalist Law and Justice (PiS), currently with the mildly eurosceptic European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group, has said it was ready for talks on an alliance with the League.

Though the number of eurosceptic deputies looks insufficient to block legislation in a vote of the EU parliament

Although the chamber looks as though it will remain dominated by centrist and liberal forces, the nationalists could achieve some gains on some issues with the right alliances, observers say.

One view is that some members on the right could be drawn further to the right by the stronger presence of the far right and this might have an impact on issues around human rights and democracy.

The European People’s Party (EPP), a transnational bloc composed of other political parties of the centre-right, is one of the groups that could be drawn further to the right.

Hungary’s Victor Orban, who with 52 per cent of the Hungarian vote won 13 seats in the EU parliament, is seen as most likely to quit the EPP, from which his party has already been suspended over concerns on rule of law in Hungary.

If he joins Salvini and his group, it could present a challenge to the European pro-EU establishment.

Italy’s former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, whose Forza Italia party has won eight seats in the EU chamber, has also repeatedly called for the EPP’s shift to the right.

Vox, Spain’s new far-right party, could also side with Salvini’s group on some issues.

But there are divisions among nationalist parties which stopped them mounting a meaningful challenge to pro-EU parties in the past legislature.

Nationalists from Eastern Europe oppose Italy’s calls to share asylum seekers among EU states.

Poland’s PiS is wary of Salvini and Le Pen’s relations with Russia.

And on economic policies, eurosceptics have widely differing views.

Observers say the rise of Euroscepticism is partly due to the success of Farage’s Brexit Party, which with 29 seats is the largest in the new parliament. But it could be only a temporary gain, as British deputies will have to quit once Britain leaves the EU.

Laurie Nowell

AMES Australia Senior Journalist