Humanity’s longest migration revealed

A new study has revealed humanity’s longest migration in a multigenerational trek of over 20,000 kilometres from northern Asia to the southern-most parts of the Americas.

The study, which involved genetic analysis of more than 1500 people from almost 140 ethnic groups, shows people travelling over multiple generations from North Asia using ice bridges to reach as far south as Tierra del Fuego.

The study, which involved genetic analysis of more than 1500 people from almost 140 ethnic groups, shows people travelling over multiple generations from North Asia using ice bridges to reach as far south as Tierra del Fuego.

Published in the journal ‘Science’, the study found that people got to the northwestern tip of South America about 14,000 years ago.

They then split into groups with some staying in the Amazon and others moving into an area known as Dry Chaco. Some continued onto the ice fields of Southern Patagonia or the peaks and valleys of the Andes.

The researchers analysed patterns of ancestry and shared DNA sequences to show how various groups moved, adapted, and split apart as they encountered new environments during their journey.

The study involved universities across the globe and was led by Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University (NTU).

Lead author Associate Professor Kim Hie Lim, of NTU, said that as people migrated, they also encountered many environmental challenges, which they mostly overcame.

“Those migrants carried only a subset of the gene pool in their ancestral populations through their long journey. Thus, the reduced genetic diversity also caused a reduced diversity in immune-related genes, which can limit a population’s flexibility to fight various infectious diseases,” Prof Lim said.

“This could explain why some Indigenous communities were more susceptible to illnesses or diseases introduced by later immigrants, such as European colonists. Understanding how past dynamics have shaped the genetic structure of today’s current population can yield deeper insights into human genetic resilience,” he said.

The research was supported by the GenomeAsia100K consortium, a not-for-profit campaign to analyse Asian genomes as a way of advancing precision medicine and biomedical research.

The study shows that a greater diversity of human genomes is found in Asian populations, not European ones, as has long been assumed due to sampling bias in large-scale genome sequencing projects.

“Genome sequencing of 1537 individuals from 139 ethnic groups reveals the genetic characteristics of understudied populations in North Asia and South America,” the research paper says.

“Our analysis demonstrates that West Siberian ancestry, represented by the Kets and Nenets, contributed to the genetic ancestry of most Siberian populations.

“West Beringians, including the Koryaks, Inuit, and Luoravetlans, exhibit genetic adaptation to Arctic climate, including medically relevant variants. In South America, early migrants split into four groups—Amazonians, Andeans, Chaco Amerindians, and Patagonians – 13,900 years ago.

“Their longest migration led to population decline, whereas settlement in South America’s diverse environments caused instant spatial isolation, reducing genetic and immunogenic diversity. These findings highlight how population history and environmental pressures shaped the genetic architecture of human populations across North Asia and South America,” the paper says.

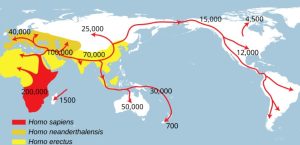

Modern humans are thought to have walked out of Africa about 60,000 years ago and kept migrating until they populated every habitable part of the planet.

Scientists say how far and fast they travelled depended on climate, the pressures of population, and the invention of boats and other technologies.

Less tangible qualities, such as imagination, adaptability, and an innate curiosity about what lay over the next hill, also accelerated their progress.

Read the full research report: From North Asia to South America: Tracing the longest human migration through genomic sequencing | Science