Is decreased migration slowing the economy?

The rapid slowing down of growth in overseas migration to Australia is fuelling concerns for the nation’s economy.

The rapid slowing down of growth in overseas migration to Australia is fuelling concerns for the nation’s economy.

New data that shows less and less people are making Australia their new home questions what this means for our economic prospects and the shortage of skilled workers.

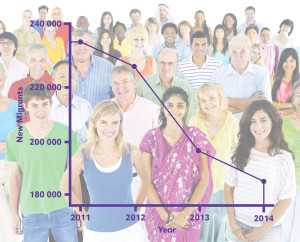

Recent data from the Bureau of Statistics reveals that last year the net overseas migration figure was 184,100 people, which is a decrease of 15% from 2013.

The data also shows that overseas migration had reached its peak in 2008, steadily dropping since then.

And as Australia’s mining-investment boom winds down, the central bank has been relying on a steady flow of new migrants to boost the economy – a stimulant most developed nations lack.

But the country’s appeal is now waning as wages stagnate and its jobless rate climbs above the US level. The population is on track for the slowest growth in nine years- a danger signal for an already faltering economy, according to economists.

An expanding population and record-low interest rates are lynchpins for the Reserve Bank of Australia’s forecast that growth will pick up to its long-run average of about 3 per cent.

Without rising ranks of new workers to boost consumption and buy the growing number of newly constructed houses, the economy’s recovery is that much trickier.

Australia’s population growth slowed to 1.4 per cent in 2014 – double the average of countries in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development but down from 1.8 per cent two years earlier. The slowdown is at odds with the RBA’s May forecast for a 1.7 per cent gain in working-age population this year.

“This suggests the Australian economy will likely fall short of the current growth path expected by policy makers in the near term and thus justifies some further easing,” said Tim Toohey, chief economist for Goldman Sachs in Australia.

The slowing down of overseas migration can’t be pinpointed to one clear cause, as various ‘push and pull factors’ influenced the rate of this movement, said the bureau’s director of demography, Denise Carlton.

The result however, is less murky than the cause, with key businesses calling for increased migration tactics to fill the skilled worker gap.

Alongside fewer migrants, the natural increase in population also slowed last year to the weakest since 2006. And there is the potential for a housing glut as population growth slows.

Revised demographic estimates from Goldman Sachs point to an excess of 75,000 dwellings by 2017, rather than a previously forecast shortfall of 140,000.

The Australian Industry Group (AIG) recognised the threat last year when they asked the federal government to increase the annual migration intake by 15%.

AIG made the call after identifying an urgent need for skilled workers due to an upturn in residential and commercial construction.

Both increasing and persistent skill shortages across key parts of the nation’s economy means increased migration needs to be considered, said AIG Chief Executive Innes Willox.

“The Australian workplace productivity agency has indicated that Australia will need an increase of 2.8 million people with quite specific skills over the next decade to fill the gaps,” Mr Willox said.

Mr Willox said the quickest and most efficient solution to fill those gaps was to bring people with those specific skills to Australia.

“There’s always debate in Australia about levels of migration and the skills component of that is about 70%,” he said.

Given that 70% of current migrants per year are skilled workers, the increased migration solution seems to fit the requirements.

As Australia is an ageing population, it is essential to address employment problems now, said Mr Willcox.

“Our demographics show that we’re getting older and almost ten per cent of our workforce is now aged over 60 so we need to replenish our workforce stocks and these are areas of great concern to us. If we don’t take steps now, these problems will just accumulate over the years ahead,” he said.

Along with opening borders up to migration, skilled refugees could be an untapped solution to the problem.

According to the UNHCR’s latest figures from mid-2015, 19.5 million people are classed as verified refugees.

Of these, only 1% of refugees are able to be resettled in another country, based on the number of refugees compared to the available resettlement allocations.

Globally, only 1% of refugees get resettled to countries like Australia and the USA, with very few of those entering back into their trained profession.

Rohana Abdullah-Wendt, from the Queensland University of Technology Business School, conducted a research study that analysed the underutilisation of skilled migrants and refugees.

“Immigrants and refugees from non-main English speaking countries are particularly impacted by employment issues regardless of the skills and qualifications acquired in their country of origins,” said Ms Abdullah-Wendt.

Skilled refugees are often forced into jobs well below their ability due to language barriers and lack of funding to enlist in qualifications to meet Australian requirements.

However, the cost of providing further education may not be a significant factor in enabling refugees to recommence their profession in their new home.

The Council for Assisting Refugee Academics (Cara), a leading UK refugee charity, calculated that to prepare a refugee doctor to practice in the UK it can cost 2.5% of what it would to train a doctor from scratch.

While adequate training for young Australians is important, clearly there is a quicker and possibly more cost effective method to fixing the problem in the time that is required.

Increasing Australia’s intake of refugees and creating efficient education programs to re-skill them for Australian standards could be a part of the solution to fill the widening gap of skilled workers.

Whichever way the skilled professional issue is addressed, the importance of increased migration to sustain economic growth cannot be understated.

Earlier this month the Swedish minister for migration, Morgan Johansson, spoke about the contribution refugees can make to the country in which they are resettled.

“The refugees who come here today may be our future doctors, political scientists, and singers,” Mr Johansson said.

“We need to keep that perspective.”

Ruby Brown

AMES Staff Writer