Learning languages the Roman way

Ancient Latin textbooks which helped Greek-speakers learn the language of their Roman conquerors are being used to inform the way second languages are taught today.

The Latin texts lay out everyday scenarios to help their readers get to grips with life in a Roman world and include subjects ranging from visiting public baths to being late for school.

Ancient Latin textbooks are informing the way second languages are taught today

They are the work of Professor Eleanor Dickey, of the University of Reading in the UK, who travelled Europe looking for scraps of remaining ancient Latin school textbooks – known as ‘colloquia’ – which were used by young Greek speakers in the Roman Empire learning Latin between the second and sixth centuries AD.

The manuscripts, brought together by Prof Dickey and translated into English for the first time show the language learners how to deal with getting to school late; a is boy told that “yesterday you slacked off and at midday you were not at home”.

However, he successfully escapes censure by putting the blame on his very important father, whom he had accompanied “to the praetorium” where he was “greeted by the magistrates, and he received letters from my masters the emperors”.

The texts also include scenarios about how to deal with visits to sick friends and preparations for dinner parties.

They are also briefed on trips to the market to wrangle over prices: “How much is the cape?” “Two hundred denarii.” “You’re asking a lot; accept a hundred denarii”…

Prof Dickey said the texts were very commonly used.

“We know this because they survive in lots of different medieval manuscript versions. At least six different versions were floating around Europe by 600 AD,” she said.

“This is actually more common than many better-known ancient texts: there was only one copy of Catullus, and fewer than six of Caesar. Also, we have several papyrus fragments – since only a tiny fraction survive, when you have more than one papyrus fragment, for sure a text was popular in antiquity.”

“We don’t know if they would have role played the scenes with other students but my hunch is that they did,” said Prof Dickey, a Classics scholar.

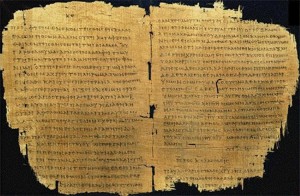

The oldest versions of the texts exist as fragments on papyri in Egypt, where the climate meant they survived.

Because of the size of these fragments, Prof Dickey had to refer to medieval manuscripts from across Europe.

“They have been copied and copied over many centuries, with everyone introducing more mistakes, so they’re not that readable. As an editor, I had to find all the different manuscripts and try to work out what the mistakes were, so I could get to the original text,” she said.

Prof Dickey also reveals how the students had glossaries to help them get to grips with the new language, collecting together lists of words on useful subjects such as sacrifices and fortune telling.

“So ’exta’ means entrails, ‘victimator’ is a calf-slaughterer and ‘hariolus’ is a soothsayer or entertainment,” she said.

“They’re definitely not the same sorts of words as we’d need today,” Prof Dickey said.

“When we think of the Romans, it’s mainly of the rich and famous generals, emperors and statesmen,” Prof Dickey said.

“But those people are clearly atypical: they’re famous precisely because they were remarkable. Historians try to correct this bias by telling us about the masses of ordinary Romans, but rarely do we have works written by or about these people.

“These colloquia give us real, contemporary stories about their lives and I hope my work gives a fairer and truer vision of ancient society.”

The texts will be published in Prof Dickey’s forthcoming book ‘Learning Latin the Ancient Way: Latin Textbooks in the Ancient World’.

Skye Doyle

AMES Australia Staff Writer