Media project empowers unfairly maligned ethnic community

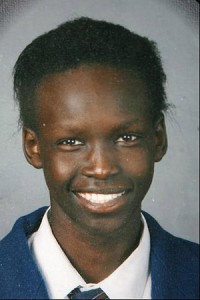

A school picture of teenage Melbourne bashing victim Liep Gony.

A unique project to analyse media representations of Melbourne’s Sudanese community while giving community members a public voice through media training has had some success in giving the community a voice and provided a model for other minority groups, according to new research.

The AuSud Media Project 2011-2013 was born out of concern over negative depictions of the Sudanese community in the Melbourne media.

Since 2005 the Sudanese community had become the target of police racial profiling operations against robberies and violence leading to a number of young Sudanese men taking successful legal action against the police under racial discrimination laws.

Then in 2007, 19-year-old Sudanese student Mr Liep Gony was fatally bashed by two white men at a railway station in Noble Park. The first media reports on the incident inaccurately said Mr Gony was murdered by a gang of Sudanese youths.

At the time, the then Minister for Immigration Kevin Andrews observed that some immigrant groups “don’t seem to be settling and adjusting into Australian life as quickly as we’d hope”.

Melbourne University’s Centre for Advancing Journalism launched the project with the help of Swinburne and La Trobe universities and settlement agency AMES.

The project was aimed at: analysing media representations of Sudanese people in Australia; discovering how this affects their everyday lives; training them in media skills to give them a voice; and, assessing whether this approach could help empower other newly arrived immigrant communities.

A report on the project found it gave participants some connections with, and insights into, the institutional life of their new society and provided them with the foundations for developing a sustainable media platform for their community.

“In these ways, the project did contribute to the empowerment of an oppressed community. It also generated amity among the disparate elements of the Sudanese community who participated, and a touch of healing in their feelings towards the wider Australian society,” the report said.

“The main lesson is that a top-down process like this runs into ownership problems. And these can be fatal to sustainability. Conversely, a bottom-up process, where the design is driven by the articulated needs of the community, and where it is hooked into an existing community-based resource, is likely to avoid the ownership problem and therefore is more likely to be sustainable,” it said.

“Overall, the training program provided a considerable number of newly arrived people, many of whom had had traumatic experiences and who had mixed levels of English-language proficiency, with some enhanced skills in writing, improved oral and written-English skills, some connections with, and insights into, the institutional life of their new society, and the opportunity to develop a sustainable media platform for their community.

“These are not inconsiderable achievements. While it is true that the website project seemed unlikely to be sustained without continuing support from the University or some other external funding source, the research team feels justified in saying that a considerable amount of good was done through this work,” the report said.

Helen Matovu-Reed

AMES Staff Writer