Politicisation of migration issues as old as the hills – study says

Disputes over migration and its political weaponisation is as old as the human race, a new research paper claims.

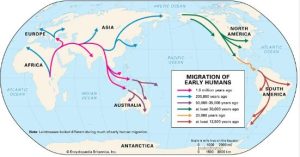

Researcher Deborah Barsky says that globalisation in the modern context, including large-scale migrations and the modern notion of the “state,” traces back to Eurasia in the period when humans first organized themselves into clusters behind boundaries.

The paper, titled ‘The Ancient Patterns of Migration – Analysis’, says that the triggers that may first have prompted human populations to migrate into new territories were probably biological and subject to changing climatic conditions.

But later, and especially after the emergence of Homo sapiens, the impulse to migrate assumed new facets linked to culture.

Writing in the journal Eurasia Review, Ms Barsky said: “The archaeological record shows that after the last glacial period—ending about 11,700 years ago—intensified trade sharpened the concept of borders even further. This facilitated the control and manipulation of ever-larger social units by intensifying the power of symbolic constructions of identity and the self.

“Then as now, cultural consensus created and reinforced notions of territorial unity by excluding “others” who lived in different areas and displayed different behavioural patterns,” said Ms Barsky of the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution.

“Each nation elaborated its own story with its own perceived succession of historical events. These stories were often modified to favour some members of the social unit and justify exclusionist policies toward peoples classified as others,” she said.

“… the frictions provoked by migration are not new problems; they are deeply embedded in human history and even prehistory. Taking a long-term, cultural-historical perspective on human population movements can help us reach a better understanding of the forces that have governed them over time, and that continue to do so.

“By anchoring our understanding in data from the archaeological record, we can uncover the hidden trends in human migration patterns and discern (or at least form more robust hypotheses about) our species’ present condition—and, perhaps, formulate useful future scenarios.”

Ms Barsky said that by the end of the last glacial period and into the Neolithic period… when sedentarism and, eventually, urbanism began peoples were defining themselves through distinct patterns and standards of manufacturing culture, divided by invented geographic frontiers.

She said that within these frontiers people united to protect and defend the amassed goods and lands that they claimed as their own property.

“Obtaining more land became a decisive goal for groups of culturally distinct peoples, newly united into large clusters, striving to enrich themselves by increasing their possessions,” her paper says.

“As they conquered new lands, the peoples they defeated were absorbed or, if they refused to relinquish their culture, became the have-nots of a newly established order.”

Ms Barsky says the current rise of nationalistic and populist movements across the globe has its foundations in ancient societies.

“After millions of years of physical evolution, growing expertise, and geographic expansion, our singular species had created an imagined world in which differences with no grounding in biological or natural configurations coalesced into multilayered social paradigms defined by inequality in individual worth—a concept measured by the quality and quantity of possessions,” she wrote.

“Access to resources—rapidly transforming into property—formed a fundamental part of this progression, as did the capacity to create ever-more efficient technological systems by which humans obtained, processed, and exploited those resources.

“Since then, peoples of shared inheritance have established strict protocols for assuring their sense of membership in one or another national context. Documents proving birthright guarantee that “outsiders” are kept at a distance and enable strict control by a few chosen authorities, maintaining a stronghold against any possible breach of the system.

“It should be no surprise, then, that we are also experiencing a resurgence of nationalistic sentiment worldwide, even as we face the realities of global climate deregulation; nations now regard the race to achieve exclusive access to critical resources as absolutely urgent.

“The protectionist response of the world’s privileged, high-income nations includes reinforcing conjectured identities to stoke fear and sometimes even hatred of peoples designated as others who wish to enter “our” territories as active and rightful citizens,” Ms Barsky wrote.

She says that climate change may see a new category of reasons emerge to justify the exclusion of migrants.

“What referents of exclusion will we invoke to justify the refusal of basic needs and access to resources to peoples migrating from inundated coastal cities, submerged islands, or lands rendered lifeless and non-arable by pollutants?” she asks.

Read more: The Ancient Patterns Of Migration – Analysis – Eurasia Review