Seven million refugee children missing out on school

More than half of the world’s 14.8 million school-aged refugee children are currently missing out on schooling, according to a new report by the UN’s refugee agency

The 2023 UNHCR Refugee Education Report says that more than seven million refugee children are at risk in terms of their future prosperity.

Also at risk is the attainment of global development goals, according to the report published by UNHCR.

The report draws on data from more than 70 refugee-hosting countries to provide the clearest picture yet of the state of education among refugees globally.

It reveals that by the end of 2022, the number of school-aged refugees jumped nearly 50 percent from ten million a year earlier, driven mostly by the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. An estimated 51 percent – more than 7 million children – are not enrolled in school.

Refugee enrolment in education varies dramatically by education level in reporting countries, with 38 percent enrolled in pre-primary level, 65 percent in primary, 41 percent in secondary, and just 6 percent in tertiary.

Refugee enrolment in education varies dramatically by education level in reporting countries, with 38 percent enrolled in pre-primary level, 65 percent in primary, 41 percent in secondary, and just 6 percent in tertiary.

In all but the lowest-income states, the difference between enrolment rates among refugees and non-refugees is stark, with far fewer refugees attending school, showing how lack of access stymies opportunity.

“The higher up the educational ladder you go, the steeper the drop-off in numbers, because opportunities to study at secondary and tertiary level are limited,” said Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees said.

“Unless their access to education is given a major boost they will be left behind. This will not help meet other goals for employment, health, equality, poverty eradication and more.”

With 20 percent of refugees living in the world’s 46 least-developed countries and more than three-quarters living in low- and middle-income countries, the costs of educating forcibly displaced children fall disproportionately on the poorest.

“We need fully inclusive education systems that give refugees the same access and rights as host-country learners,” Mr Grandi said.

“Where refugee-hosting countries have implemented such policies, they need predictable, multi-year support from global and regional financial institutions, high-income states, and the private sector. We cannot expect overstretched countries with scarce resources to take the task on by themselves.”

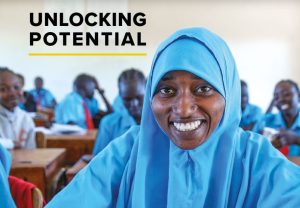

This year’s report, titled ‘Unlocking Potential: The Right to Education and Opportunity’, not only reveals the scale of the challenge of refugee education but also the extent of the potential of school-aged refugees when their access to education is secured.

The report highlights examples of refugee learners from Afghanistan, Iraq and South Sudan, who have overcome obstacles, seized opportunities and excelled.

It also takes a deep dive into the educational situation for school-aged refugees in the Americas and from Ukraine.

And it proposes important steps that donors, civil society, other partners, and refugee-hosting States can take together to support refugee education.

Among the positive global developments identified include near gender parity among refugee learners on average when it comes to access to education in reporting countries (63 percent for males and 61 percent for females at the primary level, and 36 percent for males and 35 percent for females at secondary), although data for individual countries reveals that some still have significant gender gaps.

There is also evidence from national examinations that refugee learners excel when given access to quality education.

If refugees are left behind, the UN Sustainable Development Goal of ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education for all will not be achieved, but when school-aged refugees are given access to education, they can thrive, with benefits for individuals, host states, and home countries.

The report found only around half of Ukrainian refugee children were enrolled in schools in host countries, for the 2022-2023 academic year.

The factors contributing to low enrolment rates include administrative, legal and language barriers and a lack of information on available education options, the report said.

It cited the fact that many parents are hesitant to enrol their children in host countries as they hope to return home soon to Ukraine and uncertainties about eventual reintegration into the Ukrainian education system.

Also, many countries of asylum often lack the physical space or number of teachers to take on more pupils, particularly lower income states.

“With the ongoing full-scale war in Ukraine, major efforts are required to avoid long-term damage to children’s learning, potential and prospects,” UNHCR spokesman William Spindler said.

“Unless urgent action is taken, hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian refugee children will continue to miss out on education this year,” he said.

Read the full report: UNHCR Education Report 2023 – Unlocking Potential: The Right to Education and Opportunity | UNHCR