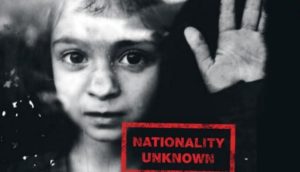

Statelessness an invisible problem

There are at least ten million inhabitants of our planet – and possibly millions more – who are not recognised as citizens of any nation, a conference on refugees has heard.

There are at least ten million inhabitants of our planet – and possibly millions more – who are not recognised as citizens of any nation, a conference on refugees has heard.

The Refugee Alternatives Conference held in Melbourne this week heard that United Nations’ data that shows there are 10 million stateless people in the world is probably a gross underestimate.

Professor Michelle Foster, from Melbourne University’s Law School, told the conference that international law defines a statelessness person as someone “not recognised as a national by any country”.

Professor Foster said most stateless people were not refugees in the traditional sense but were living in the country of their birth.

“So, for example, the Rohingya people living in Burma are not recognised as citizens by the government gf Myanmar,” she said.

“These people are invisible in a way because they are not outside the borders of their country seeking protection.

“We believe the major cause of statelessness is discrimination and 75 per cent of stateless people are minorities,” Prof Foster said.

The conference heard of the plight of the Bihari people in Bangladesh. The Bihari are an Urdu-speaking minority who have been discriminated against by the Bengali majority in Bangladesh since the country split from Pakistan in 1971.

Lawyer and activist Khalid Hussain, of the Council of Minorities, Bangladesh, told of the 30-year fight to win citizenship rights for the 300,000 Beharis living in country.

“We Beharis were regarded as stranded Pakistanis and not as Bangladesh citizens,” Mr Hussain said.

He said that after a 38-year struggle, in May 2003, a High Court ruling in Bangladesh allowed himself and nine other Bihari refugees to obtain citizenship and voting rights.

“It was a silly mistake because it applied to just ten of us. We wanted the court to give rights to all Biharis,” Mr Hussain said.

He said the fight for voting rights and citizenship continues.

Last year, an international initiative was launched with the aim of improving the circumstances of an estimated 10 million stateless people around the world.

The Statelessness Network Asia Pacific (SNAP) was launched at the Conference on Addressing Statelessness in Asia and the Pacific, in Malaysia, last November.

Its aims are to prevent and resolve statelessness in Asia and the Pacific.

It has the stated specific goals of: building solidarity and cooperation between stateless communities, civil society organisations, and other stakeholders working on issues around statelessness; developing and supporting initiatives that promote solutions to statelessness as well as increasing knowledge and visibility; and, understanding on the right to nationality and the issue of statelessness.

SNAP founding member Ramesh Kumar said the UNHCR had estimated that statelessness affects at least 10 million people worldwide, with the highest concentration of stateless persons in the Asia Pacific region.

“Populations who are stateless, or at risk of statelessness, often have limited or no access to basic human rights such as education, employment, housing, and health services,” said Mr Kumar, who is also on the organisation’s governance board.

“Also they are at a heightened risk of exploitation, human trafficking, arrest and arbitrary detention because they have difficulty proving who they are or links to a country of origin,” he said.

“Stateless people, and those at risk of statelessness, are also often unable to pay taxes, buy and sell property, open a bank account, legally marry, or register a birth or death. Statelessness can also be a cause and consequence of forced migration,” Mr Kumar said.

There are six countries in which the number of stateless persons is reported to be over 10,000 and a further nine which are currently marked by an asterisk in UNHCR’s statistics.

Major populations of stateless people can be found in India, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan and Myanmar.

And the world’s most significant stateless refugee populations include Black Mauritanians, Faili Kurds, stateless Kurds from Syria and Rohingya refugees.

Laurie Nowell

AMES Australia Senior Journalist