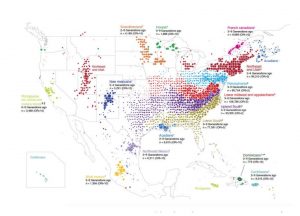

US migration revealed through genetics

Ground breaking research using genetic data from more than 777,000 people has yielded unprecedented insights into human migration and how populations come to be located where they are.

The research, which in this instance focuses on migration flows to the US over 300 years, reveals a genetic portrait of the greatest migrant nation in world history.

And it could yield advances in medical research because the DNA data also identifies predispositions to some diseases among genetically linked populations.

And in politically divided times in the US and elsewhere, the study is also a reminder that we have all come from somewhere else.

And in politically divided times in the US and elsewhere, the study is also a reminder that we have all come from somewhere else.

The study, published in Nature Communications, used data from DNA-testing company Ancestry, which has more than three million customers in its data base.

Each of these individuals has provided saliva containing DNA.

The researchers used the information to make a network of genetic connections and then used analysis techniques to identify clusters of individuals.

By using 20 million user-generated genealogical records, they then annotated these clusters to infer patterns of migration and settlement.

The use of genetics to track human migration history has been done before but never on this scale.

The study is able to pinpoint, for example, a particular region of France that French Canadians came from generations ago, where they subsequently settled in Canada, and then how they spread to North America.

It shows the genetic landscape of post-colonial America has been shaped by many factors, including war, slavery, disease, and climate change.

But the researchers were surprised by one particularly large influence – the Mason Dixon line.

The Mason-Dixon Line is a boundary line that was initially constructed to settle an 80-year land dispute between two colonies. It then became a symbolic divider of slave states from non-slave states during the Civil War.

In addition to demographic insights, the research could contribute to targeted biomedical research. For instance, they found that in certain clusters, there are higher frequencies of certain disease-risk variants.

The African American cluster, for example, has a risk for prostate cancer that has a frequency of 5.6 percent, but is rare outside the cluster at only 0.1 percent. The Finnish have a protective propensity for squamous cell lung carcinoma that is 10 times more common in their cluster.

Laurie Nowell

AMES Australia Senior Journalist