Asylum seeker’s ten years in limbo ends

“Finally there is hope for us”.

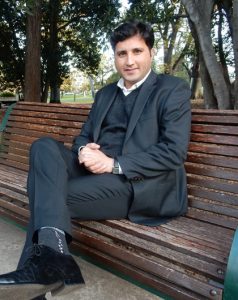

That’s how Afghan asylum seeker Obaidullah Mehak described the recent move by the federal government to grant permanent visas to 19,000 people seeking asylum in Australia.

“There is hope finally but it has cost a lot. I’ve lost ten years of my life. Years when I could have bought a house, had a family and built some memories. I’ve also spent ten years separated from my family,” Mehak said.

A lawyer and human rights activist, Mehak was forced to flee Afghanistan in 2013 after

falling foul of the Taliban and powerful warlords.

His worked in high-level jobs in his home country; he had advised the Afghanistan government on policy, electricity, telecommunications, and was instrumental in setting up a justice system to address the opium trade.

Later, he moved into human rights, specifically advocating for the rights of women and children in Afghanistan, he said he had also “risked his life” to free two Australian soldiers who had been kidnapped.

Less than a month before Mr Mehak was due to speak at a United Nations conference in Indonesia on behalf of the Afghan Civil Society in 2013, he was shot twice.

Less than a month before Mr Mehak was due to speak at a United Nations conference in Indonesia on behalf of the Afghan Civil Society in 2013, he was shot twice.

Once in Indonesia he realised that if he returned to his home his death was “certain”.

“I never wanted to leave Afghanistan, I was doing well, I had name, fame, and was passionate about my work and making a difference in the lives of so many,” he said.

But with no other choice, he left Indonesia without his family on a boat to Australia.

After being held in detention in Darwin, Mehak arrived in Melbourne.

He was “grateful” for being allowed to stay Australia, but he became frustrated at the restrictions on his life.

Mehak said he was living in overcrowded housing, became sick, depressed, and experienced racism that he was scared of reacting to, because he was afraid of the attention of the justice system.

“That visa brought hell upon us. There are days that I wouldn’t go out because I was scared of being perceived as doing something wrong, my life was frozen, it was imprisonment,” he said.

“The door was shut, and I was in absolute darkness.”

For ten years he was unable to pursue his goals, first being unable to work, then being unable to afford the $70,000 international student tuition for further study, and un-hirable his field of expertise because of his temporary visa.

“Between 30 and 40, that’s where you either make it or you fail. I don’t have a house, I have nothing. I had much bigger dreams,” he said.

But Mehak is now more hopeful that things will improve once he obtains a permanent visa.

“I want to complete a higher education degree, I want to establish a business as well as work for a really good cause. I want to bring my family over, I want to live with my family after all these years,” he said.

“I want to be able to travel freely, I want to really feel freedom for the first time in the past ten years. I want to feel free.”

CEO of refugee settlement agency AMES Australia Cath Scarth said the government’s visa announcement was a welcome and sensible move.

“The announcement will give certainty to people who have been living in limbo in Australia for many years. It will allow so many people to become full members of society and contribute fully in the life of the nation,” Ms Scarth said.

“I came here with big dreams and ambitions for the future,” Mehak said.

“But there have been so many missed opportunities. Every ladder I’ve tried to climb has come to full stop because I didn’t have permanent residency.

“I was selected to do an MBA at Melbourne Business School at Melbourne University but I had to withdraw because I couldn’t afford the fees.

“Professionally and financially, I have lost a lot but also health wise. I have had to work in underpaid jobs and I’ve had a constant fear of being kicked out.”

Mehak completed a professional translators’ course and worked for the Victorian Government during COVID-19 pandemic delivering health messaging to the Afghan community.

“It was wonderful to be able to contribute in that way but since the pandemic I have not been able to work for the agencies who have the most work because of my visa status.”

But he said the visa decision was like “spark” reigniting his life.

“It has lit things up a bit. I still feel fear but at the end of the day it’s a good thing that has happened,” Mehak said.

Mehak has a mother and wife in Pakistan, where they fled in September 2021 when the Taliban seized back power in Afghanistan.

In April last year he travelled back to Pakistan, largely illicitly, to see his mother, whom it was feared was dying from illness.

“I was desperate to get to Pakistan but I was not able to get visa. I managed to get a visa to Iran and I travelled illicitly from Iran to Afghanistan and then to Pakistan.

“It was scary. If my enemies in Afghanistan had known I was there, I would have been killed. I was condemned by the Taliban Council when I first left Afghanistan.”

Mehak sneaked into Afghanistan and obtained a passport through a friend. He then paid $US1000 for a visa for Pakistan, where he spent three months with his mother as she recovered.

On his return journey, he was beaten up when he crossed the border back into Afghanistan and he was detained at Tehran airport while trying to catch an Australia-bound flight.

“I was stopped by the Iranian police when they discovered I had two passports – an Afghan passport and my Australian travel document,” Mehak said.

“I thought that might be the end and they would lock me up. But I explained my situation and by a miracle, they let me go.”

He was stopped again on arrival back in Australia.

“Again, I thought I would be locked up but I explained my situation and they let me go.

“I felt like I had no choice in any of this. I just had to get to my mother.”