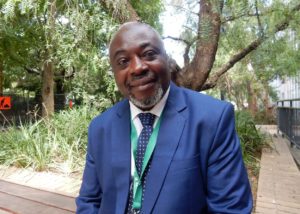

From Kinshasa to Korea – a refugee’s journey

As almost the only black man walking the streets of the South Korean capital Seoul, Congolese refugee Yiombi Thona saw first-hand race-based prejudice, fear and scorn.

As almost the only black man walking the streets of the South Korean capital Seoul, Congolese refugee Yiombi Thona saw first-hand race-based prejudice, fear and scorn.

But with courage, hard work, perseverance and a liberal dose of his idiosyncratic humour, he has made a success of his own life while at the same time educating Koreans about the difficulties faced by refugees.

“Korea is a mono-ethnic society so when people saw me on the street they feared me. Some people thought I was a terrorist or a North Korean spy,” Yiombi said.

“It was like being an animal in the zoo,” he said.

Now one of South Korea’s highest-profile refugees and a professor at Gwanju University, he arrived in the country in 2002 after fleeing his native Congo under fear of arrest.

As a member of Congo’s intelligence service, he was part of a group that tried to expose government corruption but was arrested and accused of plotting a coup d’état.

Despite finally receiving refugee status from the South Korean government in 2008, it wasn’t until 2013 that he was able to find legal employment and buy a house.

For more than a decade before that, he made a living through feeding dogs in a pet shop and doing illegal factory work.

Now he works lecturing university students in Human Rights, Forced Migration, Diaspora, NGO, African Studies and Race and Gender; he is also Chair of the Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network.

His story has all the elements of an espionage thriller and a reality TV show, but at its heart it’s a quintessential refugee journey.

“My father was the king of our tribe and a medical doctor. He had studied in Belgium and set up a free hospital in our part of Congo,” Yiombi said this week on a visit to Melbourne.

“At 13 I was sent away to study at a Jesuit boarding school. It turned out that I never went back to my village and I never saw my family again,” he said.

After school the Jesuits sent him to study at university in the capital Kinshasa.

“For me it was like a lost childhood. I had no control over my life and sending a letter home could take five or six months – if it ever arrived.

Yiombi studied economics at university and then got a job with the Congolese intelligence service.

“It was a good job that paid well but the situation in Congo at the time was very bad,” Yiombi said.

He was part of a group that discovered documents revealing official corruption and was in turn accused of plotting what has become known as the ‘pantecote a coup d’état’.

The events of the time led to one of the bloodiest wars in African history.

In 1998 Congolese President Laurent-Désiré Kabila ordered the end of all foreign military presence in the country.

This meant that a battlion of elite Rwandan troops based in Kinshasa that had helped Kabila take control of the country – overthrowing one of Africa’s longest-running dictatorships, that of Mobutu Sese Seko – had to withdraw.

Along with them went James Kabarebe, a Rwandan citizen who until recently had been the Congolese army’s Chief of Staff and had masterminded Kabila’s military campaign.

Kabila’s decree ignited a powder keg. Kabarebe later invaded Congo with ethnic Tutsi supporters and Rwandan troops. Over the next decade 5.4 million people died, making the conflict the bloodiest since WWII.

As part of the affair, Yiombi was arrested with his co-accused conspirators and held for three months.

“Finally, I was released but then I was rearrested a week later. When we were released again, four of us fled the country,” he said.

“I ended up in China and I saw something about the Republic of Korea so I applied for a visa and got one.

“I didn’t know much about Korea but I thought I was headed for North Korea but when I got off the plane I discovered I was in South Korea.

“I thought I was in Pyongyang but it was actually Seoul,” Yiombi said.

“At first I was not even recognised as human. People thought I was a terrorist, a danger.

“At that time Korea had no protection for refugees. And anyway some people thought I was a North Korean spy because Congo had once had a relationship with North Korea,” he said.

Yiombi immersed himself in Korean culture and language but it took him six years to be granted refugee status. During this time he worked illegally and also went back to university because his African qualifications were not recognised.

After partially completing a Phd in Canada, Yiombi returned to South Korea and took up the issue of refugee rights.

Helped by some of his former intelligence colleagues who had fled to Europe he became an activist.

“For two years I could not get a job so went to universities and other places and handed out leaflets,” Yiombi said.

It was a popular Korean reality television show that finally changed his life.

Each week the show on KBS TV highlights someone’s particular problem and invites the viewers to help.

Yiombi’s wife and family had joined him in Korea and when he put down a deposit on a house he planned to rent, the landlord absconded with the cash.

“When the story was put on TV, I was inundated with offers of help. It was shameful to Koreans that a Korean had stolen from an African family from such a poor country,” he said.

“The boss of Samsung personally apologised to me and offered to help,” he said.

The episode changed Yiombi’s life.

“I got a job at a university and my story started to change the Korean people’s attitude to refugees,” he said.

“I appeared on peak hour television shows and spoke about being a refugee in Korea.

“I told them refugees in Korea live in an open jail. I said it was better in jail because at least you have food and blankets.

“Refugees have no job, no house, no food and no access to medical care.

“The Minister for Justice saw the show and wanted to meet me the next day. I think the whole thing changed the way Korean people see Africans and refugees.

“Soon after my lectures were full of people who wanted to see what a black, refugee looks like. I became famous,”Yiombi said.

There are now around 600 recognised refugees in Korea and about 9000 unrecognised asylum seekers.

In 2012, the country’s refugee law was overhauled, making things easier for refugees.

But the changes only went so far. While the law called for consideration of situations in refugees’ home countries, provision of interpreters, work permits for applicants and social support benefits, they didn’t stipulate a specific number of refugees the government was prepared to accept.

Now, instead of refugees being recognised in much larger numbers, applicants are now more likely to receive what’s called ‘humanitarian status’ which gives limited protection.

Yiombi says he is constantly reminded that he is an outsider in South Korean society, even though he is a legal resident.

Overseas travel for him and his family can be problematic with immigration officials quizzing him on both departure and arrival.

Yiombi says his two youngest children, born in Korea, are effectively stateless.

They are not recognized by the Congo government nor that of South Korea.

He says his children initially were victimised by local kids and some schools even refused to accept them.

Now, he says, his children are doing well and are ‘modern Koreans’.

In a way they are following in his footsteps. His three eldest kids are now minor celebrities thanks to a YouTube channel that features their humorous take on life in South Korea.

Laurie Nowell

AMES Australia Senior Journalist