New research explodes common myths about refugees

Commonly held misconceptions about refugees are the target of important new research from Oxford University which explodes many damaging myths about those forced to flee their homelands.

Commonly held misconceptions about refugees are the target of important new research from Oxford University which explodes many damaging myths about those forced to flee their homelands.

Associate Professor Alexander Betts’ work dispels popular assumptions about refugees’ dependence and economic status.

Professor Betts, head of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies at Oxford, says existing approaches to refugee assistance are simply not working.

“Around the world, crises in Syria, Central African Republic and South Sudan continue to increase the number of displaced people inside and outside international borders. More than two-thirds of refugees are in protracted exile for at least five years, often in closed camps and without the right to work or move freely,” he said.

“Current approaches often fail to recognise that refugees have skills, talents and aspirations. Despite the constraints placed on people, vibrant economic systems often thrive below the radar, whether in the formal or informal economy,” Professor Betts said

Professor Betts’ research identified five main misconceptions about refugees.

- Refugees are economically isolated

Professor Betts says refugee economies are part of complex systems that go beyond their communities and the boundaries of particular settlements. He says refugees trade across nationality groups and across international borders.

“Maize grown in settlements is exported across borders to neighbouring countries. Congolese jewellery and textiles are imported from as far as India and China. Somali shops import tuna from Thailand, via the Middle East and Kenya,” Professor Betts says.

- Refugees are a burden on host states

He says refugees make active contributions to the host economy.

“Many Ugandan business people acknowledge relying upon the presence of refugees. One fruit farmer told us: ‘It is hard to imagine Kyangwali’s economy without the refugees’ presence’,” Professor Betts says.

“Refugees buy and sell goods and services from and to Ugandan nationals. Many also create job opportunities for others, including by employing Ugandan nationals. In Kampala, 21 per cent of the refugees surveyed employ others, and of those, 40% employ Ugandans.”

- Refugees are economically homogenous

“Although there are a range of traditional income-generating activities such as farming in rural areas and running shops and restaurants, we found huge diversity,” Professor Betts says.

“In the settlements, we found Congolese cinemas, a Somali computer games parlour using recycled consoles and televisions and innovative businesses in areas such as transportation and maize milling that have scaled and often employ others. Even among farmers, income levels vary massively, with huge deviation around the mean of $29 per month.”

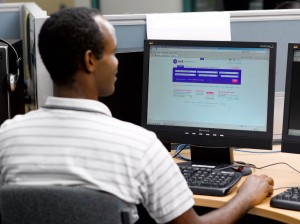

- Refugees are technology illiterate

Professor Betts says many refugees use technology, including mobile phones and the internet, for income-generating activities, often at higher levels than the national population.

“In Kampala, 96 per cent use mobile phones and 30 per cent use them for money transfers as part of their primary livelihood strategy. Many refugees also adapt their own appropriate technologies, engaging in forms of bottom up innovation, often recycling whatever is available to create an entrepreneurial opportunity,” he says.

- Refugees are dependent on humanitarian assistance

Professor Betts says refugees are far from uniformly dependent on international assistance.

“Nearly all – 99 per cent – of rural refugee households said they had at least some form of independent income-generating activity. When they were asked what kind of assistance they wanted, financial assistance did not come out top. Instead, opportunities for autonomy – including education, business training and resettlement – were valued highly,” he says.

“Although our findings are preliminary, we believe they have significant policy implications. They highlight the value of a market-based approach. Rather than assuming dependency, we need to build upon what there is to understand better refugee economies as complex systems, work to improve those markets and to empower refugees to engage better with those markets,” Professor Betts says.

“The key to this is helping refugees to help themselves. Refugees are not just passive victims. While many are in need of protection and assistance, it is important to recognise that they have capacities as well as vulnerabilities. Interventions might better nurture such capacities through, for instance, improving education, access to microcredit, business incubation and improved internet access. If we recognise and understand refugee economies, we may be able to gradually turn humanitarian challenges into more sustainable opportunities.”

Helen Matovu-Reed

AMES Staff Writer