One man’s mission to help the Burmese people

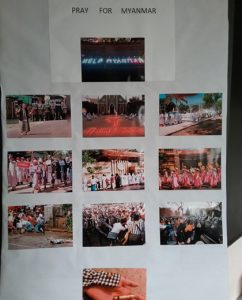

A migrant from Burma now living in Melbourne has launched a one man campaign to raise awareness about the human rights crisis in his homeland that was triggered by the recent military coup.

Hector De Santos, who turns 80 this year, has written to the Prime Minister as well as to 12 embassies of ASEAN and Asia-Pacific nations to protest the violence and authoritarian repression currently occurring in Burma.

He has also launched a Change.org campaign and written to the Victorian Council of Churches requesting they nominate a “Day of Prayer” for Myanmar.

“I’m trying to build awareness about what is happening in Burma. What the military junta is doing is terrible, it is inhuman,” said Hector, who volunteers with migrant and refugee settlement agency AMES Australia.

“I’m just trying to do something, what little I can do to make a difference,” he said.

“I’m just trying to do something, what little I can do to make a difference,” he said.

“I’m hoping that I can convince some regional government to intervene with the Burmese military,” Hector said.

In his letters to governments, he says: “With deep empathy for my fellow country people, I implore leaders of our world to exert pressure on the leaders of the Myanmar Tatmadaw Military coup for showing disregard and disrespect for the democratic wishes of the people and the duly elected NLD party and its leaders”.

“I am not involving myself much into the politics of this diabolical debacle but rather want to highlight the humanitarian side of it.

“I also plead for the immediate release of Saw Aung San Suu Kyi and members of her party, the duly and legitimately elected party.

“Please apply all trade, military and aid sanctions immediately. Channel all humanitarian aid through the many NGOs in Myanmar if still in existence.”

As well as the Prime Minister and local MPs, the letters went to the embassies and high commissions of the US, UK, India, Thailand, Indonesia, The Philippines, Israel, Vietnam and Malaysia.

Burma has been plunged into violence after the military seized control of the government on February 1 deposing the country’s ruling party the National League for Democracy (NLD) after it won a national election.

Civil protests across the country have been brutally suppressed by the military resulting in hundreds of deaths.

Civil protests across the country have been brutally suppressed by the military resulting in hundreds of deaths.

Alarmingly, Hector says his contacts in Burma have alleged that the military is abducting protesting students from the streets.

“I’m told that young woman are being grabbed off the street, sedated and raped and then dumped outside of towns and cities,” he said.

Hector has first-hand experience of oppression at the hands of the Burmese military.

“I was a victim of the military although not is such a brutal way as is happening today,” he said.

In 1962, the Burmese military staged their first coup and usurped the fledgling post-colonial democracy, heralding an era of Burmese nationalism and making Buddhism the state religion.

Under the Burmese path to Socialism, the army set about forming a Burmese identity, effectively marginalizing religious and ethnic minorities in the country.

For Hector and his family, it meant discrimination and the risk of poverty.

“They nationalised the economy and did a very bad job, so jobs were already hard to find,” Hector said.

“My Father was Portuguese and my mother was half-English, half-Indian,” he said

“We didn’t have the chance of having a future there, so we came to Australia,” Hector said.

As part of a marginalised minority in a failing authoritarian system, Hector and his future wife, Wendy, had to assess their options.

Having met Australians through his involvement in the church, they instead aimed to move to Australia where the White Australia Policy was still in place.

“They didn’t want to know your qualification, or your experience, just where your father was from,” Hector recalled.

With the Burmese government censoring letters, the pair used a friend at the British embassy to smuggle their applications out.

“The British embassy was our only real postal service,” Hector said.

“After a long time, they told us I could come, and then once I was in Australia my fiancée would be able to come,” he said.

“I told them ‘no’, we must come together or I will not come.”

Out of options and with pressure building, in 1966 they obtained a one-year travel visa and left for Thailand.

However, the Burmese government’s isolationist policies meant they could not take with them any currency or objects of value.

“All we could bring was my wife’s wedding ring, on her hand, and one of her necklaces, which I wore,” Hector said

After working for the US Navy in Thailand, Hector and Wendy came to Australia in 1969 as migrants.

“The people were very kind to us when we arrived here. Even though the government still believed in the White Australia Policy, the people were not thinking like this,” Hector said.