Refugee doctor desperate to rebuild his career

When ISIS started killing doctors and professionals and when the armed militias opposing them began demanding all of their money and possessions, Syrian medico Bashir Ahmad decided it was time to leave.

As an ethnic Kurd, Bashir felt even more vulnerable and was forced to flee the conflict in his home town of Kamishli, in north east Syria and seek sanctuary in Turkey.

As an ethnic Kurd, Bashir felt even more vulnerable and was forced to flee the conflict in his home town of Kamishli, in north east Syria and seek sanctuary in Turkey.

A specialist in internal medicine, Bashir found work in the University Hospital at Erbil, in Turkish Kurdistan.

“I had to leave my country because my life was threatened by Daesh. They were killing doctors or locking them up,” Bashir said this week.

“And the militias fighting ISIS were acting like robbers. They targeted professionals and were asking for money and taking everything,” he said.

Bashir left behind his house, a prestigious hospital job, his own medical practice and a good life when he was forced to flee.

Now in Australia on a humanitarian visa, he is trying to rebuild his life.

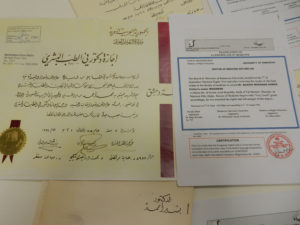

But despite a box full of medical degrees and qualifications and 32 years of experience, Bashir is finding it difficult to re-establish himself.

To practice medicine in Australia he must pass a rigorous English proficiency course called an Occupational English Test (OET).

The OET comprises units in reading, writing, listening and speaking.

Bashir has scored well in these units but the test requires candidates to listen and take notes at the same time and also to read long passages of medical text in a short period and then answer questions about them.

Bashir and many migrant doctors – often with good English skills – struggle with this.

Bashir and many migrant doctors – often with good English skills – struggle with this.

Bashir says the key is the time constraints of the tests.

“English is my fourth language after Arabic, Kurdish and French and with a little more time I could easily complete these tasks,” he said.

But Bashir is determined and hopeful of resuming his medical career.

And he has enrolled in a new program that is aimed at fast-tracking migrant and refugee professionals into work.

Called the ‘Career Pathway Pilot’, the program helps enrolees plan a career pathway and get recognition for qualifications.

Run through the federal Department of Social Services, it also facilitates work experience and upskilling on candidates.

There is a shortage of specialist doctors in Australia, including internal medicine.

Internal medicine, known as general medicine in Commonwealth countries is a specialty dealing with the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of adult diseases.

Physicians specialising in internal medicine are skilled in the management of patients who have multi-system disease processes.

Bashir says he would dearly love to work as a doctor in Australia and contribute to the country that has given him and his family refuge.

“It took two years after applying for a visa and finally I am here and I would like to practice medicine,” he said.

“I am preparing myself to work as a doctor by improving my English language skills,” said Bashir, now living in Melbourne’s east.

“It is important that people realise that those who come to Australia to work in the medical sector need special help at the beginning to get themselves into a position where they can work and contribute,” Bashir said.

He said his family has already settled in. He has a son is studying pharmacy at RMIT and a daughter doing architectural engineering at Victoria University. His youngest son is at high school.

Laurie Nowell

AMES Australia Senior Journalist