Taking on Southeast Asia’s scam gangs

For almost ten years, Saw Thura* has been one of a loose band of people and agencies fighting to expose a little-known but growing human rights crisis created by shadowy criminal gangs.

The researcher and advocate has been working to support and secure the release of the trafficked victims of brutal scammer gangs operating along the Thai-Burma border.

So far, Saw Thura has helped to free almost a thousand unwitting victims tricked into effective slavery by criminal gangs, which operate multi-million dollar online and phone scams with the acquiescence of the brutal military junta which currently rules Burma.

Now resettled as a refugee in Melbourne with his wife, father and two children, Saw Thura is continuing his humanitarian work.

His journey as an activist began when set up a small not-for-profit organisation to support displaced refugees in his region, mainly persecuted minorities such as the Karen and Chin.

His journey as an activist began when set up a small not-for-profit organisation to support displaced refugees in his region, mainly persecuted minorities such as the Karen and Chin.

The charity provides food and runs classes for refugee children.

“We started out delivering food and other aid to some of the 11,000 refugees along the border. But then we also started trying to help people who had been trafficked and kidnaped by the scammer gangs,” he said.

On one trip to deliver aid, he was shot at by the Myanmar military. He has dramatic phone footage of salvos of automatic fire flying over his head.

“We got a call from some refugees saying they had no food. We went to deliver some food, but the Burmese military shot at us. The shots came close, we could hear them zipping past us, and we were almost killed,” he said.

On another trip, a colleague was shot dead.

Saw Thura says that in recent times, more of his group’s work has been about helping trafficked people. His group and other NGOs have helped in the release of more than a thousand people in recent years.

In one recent instance, 26 Ugandans were rescued from a compound after being tricked into working for a gang of scammers.

He has also been part of research projects into the scammers for the Asia Foundation, the US Institute of Peace and Amnesty International, International Justice for Migrants; as well as research into labour issues and exploitation of migrant workers for the UK NGO Fair Square.

He has also been part of research projects into the scammers for the Asia Foundation, the US Institute of Peace and Amnesty International, International Justice for Migrants; as well as research into labour issues and exploitation of migrant workers for the UK NGO Fair Square.

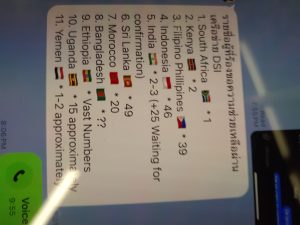

Saw Thura says the research indicates there may be as many as 77,00 victims inside the scam centres. They come from a range of developing countries, including India, Sri Lanka, Nepal, China, Bangladesh, Vietnam, the Philippines, Ethiopia, Uganda, Morrocco and other African nations.

He says that scam compounds have increased in recent years. They are run by Chinese criminal gangs who recruit IT workers from developing countries on the pretext of high-paying jobs in Bangkok.

But on arrival they are kidnapped and taken to the scam compounds across the border in Myanmar. He says the gangs are in cahoots with a section of the Myanmar military known as the Border Guard Force who take a cut of the scammers’ profits.

“They recruit people who are tech savvy and speak English from overseas. These people think they are going to proper jobs, but they end up in horrible circumstances. The Burmese police and military allow this to happen,” he said.

And the trafficked workers are beaten and tortured if they don’t meet scam income quotas. He has graphic and confronting pictures of some of the torture victims.

“It’s horrific, people are tortured; they’re beaten or electrocuted. One woman was strung up by her wrists for 48 hours and forced to keep her eyes open as buckets of water were thrown at her,” Saw Thura said.

“Some of these trafficked people have died but we don’t really know how many.”

Saw Thura said the gangs have developed corporate-like structures.

Saw Thura said the gangs have developed corporate-like structures.

“These are very sophisticated operations. They have online scams, phone scams and romantic scams. There are dedicated teams for particular countries and particular types of scams,” he said.

“So, one team, for instance, will be targeting Australia, another the US and so on. And will work to the time zones of the countries they are targeting.

“The teams are given a $US50,000 monthly target by the gang bosses. And if they don’t achieve this, they are beaten and tortured and forced to work harder.”

Saw Thura says his charity and other agencies have been trying to assist the trafficked people to escape.

“Typically, after people have been tortured or beaten, they contact their embassies in Thailand. But because the scammers are in Myanmar there is little the embassies can do so they pass on our contact details of the victims,” he said.

“The victims have access only to phones used in the scams which are monitored, so we ask them to delete all of their communications with us and to call only on their breaks.

“Often, the parents or families of the victims will pay a ransom – up to $US40,000 – to secure their release. We’ve seen families sell their houses and farms to get their people released. They pay through crypto currency, so it is not traceable.

“But some families can’t afford this and sometimes, after the ransom is paid and the person released, they are immediately trafficked to another scam gang.”

Saw Thura says he works with Karen military group known as the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA).

“The DKBA is not involved in the scams and they help us rescue people by using their influence to get them out,” he said.

Saw Thura says he has had to keep a low profile in his advocacy and support work, often moving his family from village to village to avoid the attention of the gangs.

“We worked with an expatriate Burmese media group to expose the scammers crimes. Immediately after I got a threatening call. They said ‘we know who you are’.”

That was when Saw Thura decided it was time to take his family to safety in Australia.

He said the gangs have set up networks of shell companies in Thailand, Myanmar and Singapore which has seen them set up illegal casinos, prostitution and drug dealing cells.

“There is a web of companies across Southeast Asia, making it difficult to identify illicit money,” he said.

“We have identified 73 casinos mostly in the Karen state. They are technically illegal but the authorities take a cut; it’s corruption.

“They are also into kidnapping and extortion. Just recently an Indian man who came to Chang Mai in Thailand for a job as a restaurant manager was kidnapped by one of the gangs. They want $US10,000 ransom for him,” Saw Thura said.

He says his research has shown the scammers are spreading their operations internationally.

“The scammers are spreading their operation to places like Uganda and parts of the Philippines,” he said.

Saw Thura is a member of the Gurkha minority in Myanmar. There are about 250,000 Gurkhas living mostly in the rural Chin region. They are one of the ethnic minorities who have long been persecuted by the Myanmar military.

He says he plans to continue his work now he and his family are safe in Australia.

“I want to study human rights law and continue my work helping trafficked people as well as research into this area.

“Our work has been about how we can get these gangsters arrested and get justice and compensation for their victims. And that work continues,” he said.

Global cyber scams represent the third largest economy in the world behind the US and China generating earning of up to $US trillion a year, according to Interpol.

Australians last year reported $2.7 billion lost to cyber fraud, mostly to romance scams.

The scammers have found refuge in the largely unregulated border areas on Myanmar, such as Myawaddy, and also in areas of Cambodia and Laos. Recent reports said more than 340 were operating across the region. `

*Saw Thura’s name has been changed to protect his family’s safety.