The issues behind global human suffering

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the rise of the omicron variant has drawn attention away from a plethora of humanitarian crises across the globe.

And while we see media reports about crises in places like Afghanistan and Ethiopia, there is far less attention paid to the systemic factors that underpin these human calamities. iMPACT magazine looks at some of these issues:

- An uptick in extreme poverty and hunger

The COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare massive inequalities within and between nations and economists say the start of economic recovery around the globe will, counter-intuitively, makes these differences even starker.

The pandemic increased the proportion of people living in extreme poverty, ending a two-decade downward global trend.

This will make it even more difficult for countries already dealing with conflict and widespread poverty and could broaden the need for humanitarian aid.

The pandemic increased the rate of extreme poverty – those surviving on less than $1.90 a day – by an about 97 million people, lifting the global rate from 7.8 per cent to 9.1 per cent.

The pandemic increased the rate of extreme poverty – those surviving on less than $1.90 a day – by an about 97 million people, lifting the global rate from 7.8 per cent to 9.1 per cent.

There are predictions that poverty numbers may decline, aid agencies say that this may not occur in in places where there is little access to vaccines and where these is existing international debt distress.

situation for those newly plunged into poverty may get better with time, but the economic effects will likely be felt the longest in the parts of the world that were already suffering before the pandemic.

Another factor is that it is women who have been hit the hardest by the economic losses. Across the world, they are more likely than men to be employed in low-paid, precarious jobs and many have also been forced to drop out of the labour force to do unpaid care work as a result of the pandemic.

Hunger has also been exacerbated by the pandemic.

More than 280 million people are short of food, according to the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).

About 45 million of these people are on the brink of famine – a number unprecedented in modern times.According to the New Humanitarian magazine, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Nigeria, South Sudan, and Yemen are among the countries most in need.

The magazine reports that multiple droughts in Afghanistan and southern Madagascar have reduced rural people’s ability to cope.

While aid agencies warn that the goals of the Famine Prevention Compact – agreed by the G7 in May, have not been met with less than half of the money urgently needed to ward off famine has been received.

- Political chaos

Turmoil in government and the rise of autocrats are creating fresh humanitarian needs.

Afghanistan, Haiti, and Myanmar have all seen political turmoil in the past year – with the Taliban’s return in Afghanistan, the assassination of President Moïse in Haiti and the military coup in Myanmar.

These events have worsened already critical situations.

In Afghanistan, hunger is widespread and growing and with the economy and public sectors collapsing, the entire population may plunge below the poverty line this year.

Afghanistan’s emergency appears also to be a crisis of rights – especially for women and girls who have lost two decade’s worth of gains under the Taliban. Gender-based violence is rising and women have fewer options in employment, education and healthcare.

Haiti also was dealing with a crisis before President Moïse’s murder pushed the country deeper into turmoil with rising criminal gang violence making it harder to respond to humanitarian needs.

Tens of thousands of people have been displaced, hospitals have closed and about 40 per cent of the population will need food aid this year.

Last year’s military coup in Myanmar has stirred up longstanding conflicts and ignited a nationwide civil disobedience movement and an armed resistance.

The military junta has launched violent crackdowns as well as media internet blackouts. Nearly 300,000 people have been newly displaced, at least 1,300 civilians killed and thousands more arrested.’

All this had meant a tripling of the number of people in need of emergency aid.

- Social media and online hate

Recent whistle blower revelations have confirmed that Facebook – the world’s largest news platform – amplifies hate speech.

This is having an unprecedented and deadly effect in places like Ethiopia where there has been a rise in posts calling for ethnic violence. The same is true in Myanmar.

Another deleterious effect of unfettered social media has been on election integrity.

The activist group Human Rights Watch says social media gives authoritarian governments the ability to control political conversations.

- Diminishing asylum opportunities

Many Western democracies are imposing new and more convoluted exceptions to the right to seek asylum at their borders – sometimes in clear violation of already agreed to human rights principles.

These deterrence policies are turning manageable movements of people into a series of ugly humanitarian crises at national borders while reinforcing global inequality.

In a recent border crisis on the EU’s eastern border with Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia, and Poland have deployed troops and expelled asylum seekers and migrants.

There have been deaths on the US Mexico border after US president Joe Biden appears to have reneged on promises to wind back the hard line immigration policies of his predecessor Donald Trump.

Human Rights Watch says that faced with ‘emergencies’ – which include the pandemic itself and increasing numbers crossing their borders – Western democracies have responded by blocking people’s rights to seek asylum.

The agency says this has resulted in once-respected international refugee norms and laws being eroded and asylum seekers being left in dangerous situation.

The UN’s global compacts on refugees and migration, signed three years ago, were aimed at paving the way for a more equitable sharing of the burden of resettlement and safer legal pathways for migration. The pandemic seems to have been a stumbling block to progress on these agreements.

- Health effects of rising temperatures

The health effects of climate changes –related rising temperatures are now clear.

Infectious diseases once thought eradicated have returned with broader and more deadly footprints. Heat-related deaths are on the rise – many caused by undernutrition caused by water scarcity and food insecurity.

More frequent and powerful storms and weather events as well as rising seas are contributing to humanitarian crises.

An editorial published in the medical journal The Lancet in September 2021 called this failure to rein in soaring temperatures “the greatest threat to global public health”.

The symptoms of this can been seen the globe; in shifting rainfall patterns in Pacific island nations and in changing diets in Africa where yields from traditional crops become more unreliable.

Mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue fever are presenting in ever more places.

Dengue fever has become an annual epidemic in Nepal, for example and has been recorded for the first time in Afghanistan.

- Hotspots

Afghanistan. A massive relief effort has been launched to support millions of Afghans suffering the effects of a fresh humanitarian crisis. International aid agencies and the United Nations have revealed the details of a new response plan that aims to deliver vital humanitarian relief to 22 million people in Afghanistan and support 5.7 million displaced Afghans and local communities in five neighbouring countries.

The plan comes amid fears that the collapse of the Afghan economy since the Taliban took power last August will result in wide-spread hunger, disease, malnutrition and death.

A UNHCR briefing document says people in Afghanistan face one of the world’s most rapidly growing humanitarian crises. It says half of the population face acute hunger, over nine million people are displaced and millions of children are out of school. The document says fundamental rights of women and girls are under attack, farmers and herders are struggling amidst the worst drought in decades, and the national economy is in free fall.

“Without support, tens of thousands of children are at risk of dying from malnutrition as basic health services have collapsed,” the document says.

“Conflict has subsided, but violence, fear, and deprivation continue to drive Afghans to seek safety and asylum across borders, particularly in Iran and Pakistan.

“More than 2.2 million registered refugees and a further four million Afghans with different statuses are hosted in the neighbouring countries,” it says.

Haiti. A massive earthquake in August last year plunged Haiti into desperate humanitarian crisis that it was ill prepared to meet. Around 800,000 people were affected.

There were 2,207 deaths, 12,268 people injured. More than 650,000 people, including 260,000 children, were left in need of humanitarian assistance.

Around 130,000 houses were partially or completely destroyed, 60 health facilities and 308 schools were damaged or destroyed and 81,000 people lost access to their drinking water.

The assassination of President Moïse has plunged the country deeper into turmoil with spiking gang violence making it harder to respond to humanitarian needs. It is estimated that about 40 per cent of the population of 11 million will need food aid this year.

Myanmar. The humanitarian situation in Myanmar continues to deteriorate since the military seized power in a coup in February 2021.

A United Nations report says people of Myanmar are facing an unprecedented political, socioeconomic, human rights and humanitarian crisis with needs escalating dramatically since the military takeover and a severe COVID-19 third wave.

The turmoil is projected to have driven almost half the population into poverty heading into 2022, wiping out the impressive gains made since 2005.

It is now estimated that 14 out of 15 states and regions are within the critical threshold for acute malnutrition.

For the next year, the analysis projects that 14.4 million people will need aid in some form, approximately a quarter of the population. The number includes 6.9 million men, 7.5 million women, and five million children.

Ethiopia. After months of violent clashes between federal troops and Tigrayan rebels, civilians in the Tigray region of Ethiopia are in crisis, the UN says.

Communication networks are down, banking services are halted, roads are blocked and there are shortages of basic supplies. Fearing for their lives and the lives of their families, thousands of children, women and men have been forced to flee into Sudan

More than 61,000 refugees have arrived in Sudan and are being sheltered in transit centres near the border. Water and meals are being provided but the refugee agency UNHCR has appealed for international support to feed and house the displaced.

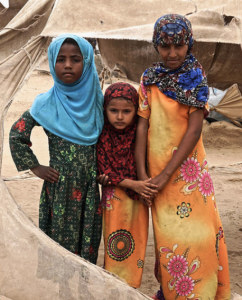

Yemen. Six years into an armed conflict that has killed and injured over 18,400 civilians, Yemen remains the largest humanitarian crisis in the world.

The Arabian Peninsula nation is experiencing the world’s worst food security crisis with 20.1 million people – nearly two-thirds of the population – requiring food assistance at the beginning of 2020.

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). The people of the DRC are suffering from the impact of one of the most complex and longest humanitarian crises.

Almost 20 million people are acutely food insecure in a country that has been dealing with the fallout of conflicts, epidemics such as Ebola, and natural disasters that have driven people out of their homes. More than 3 million children are acutely malnourished.