The rising toll of missing migrants

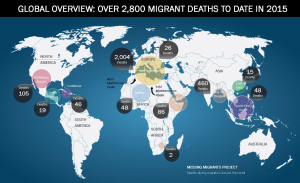

Migrant deaths globally in 2015 to date.

As global migration increases almost exponentially, many people seeking refuge from war or persecution or searching for a better life face unimaginable and often fatal perils along their journeys.

Some are ready to spend their life savings or take on massive debts and risk their lives and the lives of their families for a new start. Death is a risk worth taking in desperate situations of violence, persecution, famine or even absence of prospects of a decent life.

Last year, the world watched in horror when some 360 migrants lost their lives in the attempt to swim to the shores of the Italian island of Lampedusa.

Up to 500 more migrants met their death at sea off Malta just a few months later.

Two survivors reported that smugglers deliberately rammed and sunk their ship when migrants refused to board a less seaworthy vessel, after having been forced to switch boats at sea many times on their journey from Egypt. There were only 11 identified survivors; witnesses reported that as many as 100 children were on board.

These tragedies in the Mediterranean are but two examples of the many migrant tragedies unfolding all over the world. Hundreds perish every year on the journey from Central America to the United States through Mexico, under the desert sun or robbed and beaten along the way; migrants drown on their way from Indonesia to Australia, or off the coast of Thailand and in the Bay of Bengal.

Migrants are dying of thirst crossing the Sahara Desert into North Africa, or drowning in the Gulf of Aden as they try to reach the Middle East. In many of these cases, migrants often disappear and die without a trace.

In 2014, up to 3,072 migrants are believed to have died in the Mediterranean, compared with an estimate of 700 in 2013.

Globally, the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) estimates that at least 4,077 migrants died in 2014 and at least 40,000 since the year 2000. The true number of fatalities is likely to be higher, as many deaths occur in remote regions of the world and are never recorded. Some experts have suggested that for every dead body discovered, there are at least two others that are never recovered.

Head of the IOM William Lacey Swing says these deaths are a paradox.

“At a time when one in seven people around the world are migrants in one form or another, we are seeing a harsh response to migration in the developed world. Limited opportunities for safe and regular migration drive would-be migrants into the hands of smugglers, feeding an unscrupulous trade that threatens the lives of desperate people,” Mr Swing said.

“We need to put an end to this cycle. Undocumented migrants are not criminals, but human beings in need of protection and assistance, entitled to legal assistance, and deserving respect,” he said.

To that end, the IOM has launched the Missing Migrants Project – the only global data base sharing key data on deceased and missing migrants from around the world. The aim is to strengthen advocacy and support a more informed police response.

“Collecting and presenting information about who these migrants are, where they come from and why they move, is the first indispensable step to understanding this global tragedy and designing evidence-based, effective policy responses and practical protection measures to prevent further loss of life,” Mr Swing said.

The project is reviewing existing sources of data and showing that there are huge gaps in our knowledge.

Relatively little is known about the migrants who perish. In the case of tragedies at sea, the majority of bodies are often never found. As many migrants are undocumented, often relatively little is known about their identities, even for those whose bodies are recovered.

In 2014, nearly 70 per cent of deaths recorded by IOM refer to migrants, who are missing, usually at sea. In the majority of fatalities occurring in 2014, it was not possible to establish whether the deceased were male or female.

Information on region of origin suggests that the majority of migrants who lost their lives in 2014 were from Africa and the Middle East.

The report also shows that for some regions of the world, such as sub-Saharan Africa, reliable information is often extremely scarce, as NGOs, media and governments are not tracking migrant deaths.

The project is also finding important differences in death trends across regions.

Although methods of counting vary, over the last 20 years Europe appears to have the highest figures for reported deaths.

Since the year 2000, over 22,000 migrants have lost their lives trying to reach Europe. Between 1996 and 2013, at least 1,790 migrants died while attempting to cross the Sahara. Since 1998, more than 6,000 migrants have died trying to cross the United States–Mexico border, according to the United States Border Patrol.

In Australia, the Border Crossing Observatory of Monash University suggests that nearly 1,500 migrants died on their journey to Australia between 2000 and 2014.

Over the last year, the increase in deaths has largely been driven by a surge in the number of fatalities in the Mediterranean region. Why this is occurring is not entirely clear, but likely reflects a dramatic increase in the number of migrants trying to reach Europe.

Over 112,000 irregular migrants were detected by Italian authorities in the first eight months of 2014, almost three times as many as in all of 2013.

Many are fleeing conflict, persecution and poverty, with Eritreans and Syrians constituting the largest share of arrivals in Italy this year.

The deteriorating security situation in Libya, where many migrants reside prior to their departure for Europe, has also increased migration pressures. In response to the high flows across the Mediterranean, policy has prioritized search and rescue, with tens of thousands of lives saved this year.

The project has made a series of key recommendations on ways of improving data including an independent monitoring body should be established with representatives of governments, civil society and international organizations to promote the collection, harmonization and analysis of data on migrant deaths globally.

It has also urged that national governments should to take greater responsibility for collecting data on migrant deaths, in partnership with NGOs to ensure transparency and accountability.

Laurie Nowell

AMES Australia Senior Journalist