Refugee Melbourne: a snapshot of resettlement

The first comprehensive picture of the settlement of refugees across Melbourne has emerged from a new study that reveals where the city’s refugee population comes from, what its health and housing needs are and where its members are now living.

Titled Human Arrivals: a spatial analysis of populations distribution and health needs, the study shows that Melbourne’s recent refugee arrivals (2010 – 2015) were predominantly from Afghanistan, Iraq, Burma/Myanmar and Iran.

Meanwhile between 2001 and 2011, they came mostly from Sudan, Iraq, Afghanistan and Burma/Myanmar and refugees formed 12 per cent of all arrivals to Victoria in 2011.

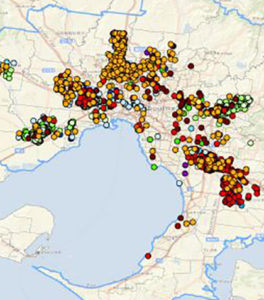

The report says large populations of refugees live in the local government areas of Greater Dandenong, Hume, Casey, Brimbank and Wyndham and each area has people from a diverse range of countries with associated language needs.

It found that refugee groups are attracted to areas with affordable housing with about two-thirds of refugee arrivals in 2011 in Victoria living in the 20 per cent most socio-disadvantaged areas in the state.

It found that refugee groups are attracted to areas with affordable housing with about two-thirds of refugee arrivals in 2011 in Victoria living in the 20 per cent most socio-disadvantaged areas in the state.

Over one quarter of people on Bridging Visa E lived in Dandenong or Doveton in 2014, the report says.

Numbers of Special Humanitarian Program visas have decreased dramatically between 2003 and 2011, similar to refugee visas which peaked in 2008-2009 and steadily decreased leading up to 2011.

“Constant changes in the policy environment particularly in terms of visa bands and associated entitlements have created confusion for both humanitarian arrivals and health service providers,” according to the report, produced by Melbourne University and the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services.

The report states language difficulties – including native language literacy, English literacy, health literacy and health service system literacy – are some of the greatest barriers to health service provision and health outcomes for refugees.

“In Victoria there is no central resource that provides information on how to access general practitioners, specialist medical practitioners or allied health practitioners that speak a language other than English,” it says.

“A considerable number of general practitioners speak a wide range of languages other than English in Melbourne but there is no resource available to link humanitarian arrivals or service providers to these medical professionals.”

It says that more resources for language assistance need to be directed towards specialist medical practitioners, mental health professionals and other health professionals working with refugees.

The report says Arabic has consistently been the most common language spoken by refugees in Victoria over the past 15 years and Arabic speakers were also commonly proficient in spoken English.

Karen speakers were the least likely new refugee arrivals to have spoken English skills.

The most common languages spoken by humanitarian arrivals to Victoria over the past 15 years are Arabic, Dari, Karen, Hazaragi and Farsi (Persian).

Arabic-speaking humanitarian arrivals are common in the northern and north-western suburbs of Melbourne while Dari, Hazaragi, Pashto and Arabic are most common in the south-east, the report says.

The report produced a series of recommendations for future policy and practice including a need to collect data to measure and monitor secondary migration of refugee arrivals in Victoria.

It also recommended that the year of arrival in Australia, country of birth and preferred language spoken are the three essential pieces of information that should be routinely collected for all humanitarian arrivals.

It says the mapped data of bilingual GPs included in the report should be made available to the general community and also expanded to include other bilingual medical practitioners and allied health workers.

The report called for additional training needs to be provided to GPs, medical practitioners, allied health professionals and front line administrative staff to build their knowledge and skills in working with refugees and interpreters.

And it said more general literacy and health literacy support was needed for humanitarian arrivals. This includes literacy in English, literacy in their native language, health literacy and literacy of the local health and hospital systems.

“Being unable to speak in a language they understand or access and interpreter they feel comfortable with further complicates these issues,” the report says.

It also says more housing support was needed for humanitarian arrivals in Victoria.

In compiling the report, the researchers used data from The Australian Bureau of Statistics Australian Census, Migrants Integrated Dataset and the AMES Australia Humanitarian Entrants Management System.

Laurie Nowell

AMES Australia Senior Journalist

Leave a Comment